The St. Bernard

The Saint Bernard is unquestionably an attention-getter. If nothing else, people will want to know how much food goes into that massive mouth each day. With large males weighing upward of 200 pounds, this is a big dog. Fortunately, with good breeding and proper care it tends to be calm and amiable, and its exercise requirements as an adult don’t begin to approach those of many smaller breeds.

Thought to be derived from the ancient mastiff-type Molosser war dogs of the Romans, the St. Bernard is a dog with a long and romantic history. The type originated in the Swiss Alps at the Hospice of the Great St. Bernard, founded in 1050 by Bernard of Menton (later canonized) of the monastic Order of St. Augustine. Situated at an elevation of 8100 feet, with such harsh winter weather conditions that snow levels can reach 36 feet and the nearby lake is often frozen year-round, the Hospice was established in part to help travelers make it through the only passage in the area linking Switzerland and Italy. Soldiers, traders, seasonal labourers and pilgrims en route to or from Rome would traverse the forbidding narrow alpine pass. The rugged terrain with its sudden weather changes, bitter cold, blizzards and avalanches posed much danger. Gangs of bandits also lurked alongside the route to plunder unprotected wayfarers. The Hospice provided welcome refuge, a fireplace, hot meal and safe bed, to frightened and road-weary travelers.

Life on White/Bigstock

To accompany them in their daily activities, the monks brought general-purpose working dogs up to the Hospice from farms in the valleys below. It is unclear exactly when the first dogs arrived, what they looked like, and what, if any, was the monks’ breeding program, as a fire in 1555 destroyed most of the Hospice including all its archives. But a painting dated around 1695 and still hanging there today shows a clear St. Bernard dog progenitor – a large white dog with brown markings and a substantial head, of powerful build and noble stance. Though certain aspects of its form have become exaggerated, today’s St. Bernard is remarkably true to his type.

The original Hospice dogs were intended for guard duty, as the monks had no other protection from the robbers. But as dogs will, they soon created new working niches for themselves. Some were used to turn the huge spit upon which meat was roasted. But more importantly, the monks discovered that these dogs had a very strong sense of smell and an uncanny sense of direction. Soon the Hospice dogs were assisting the monks with their rescue work. They dug many people out of the snow after avalanches and sometimes would even go out alone during storms to find people stuck in snow or to guide the disoriented to refuge.

The most famous rescue dog was Barry, born in 1800 and credited with saving over 40 human lives. If he could not dig somebody out of the snow by himself, he would run back to the Hospice and get help from the monks. One story tells of a dying mother, caught in an avalanche, who tied her baby boy to Barry’s back in a desperate attempt to save him. Late that night, during a last check of the outer walls of the Hospice, the monks found Barry with the nearly-frozen bundle huddled in the snow and managed to revive the boy. The dog then led the monks to the frozen body of the mother.

When Barry was twelve, he was apparently stabbed by a man caught in the snow who mistook him for a wolf as he approached. Barry returned repeatedly to the man and he was stabbed again and again. Though the monks eventually managed to nurse Barry back to health (it is not said what happened to the traveler), he was unfit to work after that and was retired. His mounted body still elicits gratitude and admiration at the Natural History Museum of Berne.

The tales of lives saved (and of many lives, both monk and dog, lost) are truly heroic – and somewhat miraculous, too, in the sense of how the dogs seemed to naturally know what had to be done in an emergency without explicit commands or instruction. Certainly the monks trained their dogs, but they did not use harsh orders or punishment, or militaristic “Me Alpha!” obedience training methods. It is likely that young dogs learned much from watching more experienced dogs, but the offspring of great rescue dogs tended also to be good workers.

Grisha-Bruev/Bigstock

As part of a 1927 course directed at St. Bernard judges, Professor Albert Heim described the dogs’ exceptional working sensibilities: “Remarkable is the intelligence of these dogs in their way of cooperating. If several dogs find a lost traveler in the snow they try to get him in an upright position. If this is not possible, two dogs lie down on each side of him to keep him warm while the others return to the Hospice and summon help. [When] the rescue party arrives, all of the dogs remain in the background so as not to interfere with the monks’ work. [When] the victim is placed on the stretcher, the dogs lead the way to back to the Hospice. No orders need to be given to the dogs.”

Today, the St. Bernard dogs are no longer used in rescue work, as Swiss avalanche rescue teams now travel by helicopter and use German Shepherds, which are smaller and lighter. Dogs are still housed at the Hospice, but more for companionship and history’s sake. (And no doubt for the many tourists who can now speed up to the top of the pass in the Audis and BMWs.) Kegs of brandy, while photogenic, were never actually carried by working dogs.

The dogs of the Hospice have had many names over the years, including Holy Dog, Hospice Dog, Cloister Dog, Butcher Dog, Alpine Mastiff, St. Bernard-Mastiff and Barryhunde, but by 1865 the name St. Bernard was in common use. The early dogs had uniformly smooth, dense coats. In the mid-1800s Newfoundlands were brought up and interbred with hospice dogs in the hope that a longer coat would better protect them from cold, but it was found that this matted in snow, causing the dogs to become coated in ice. Thus unsuitable for work, the rough-coated dogs were afterward sold or given away by the monks. Modern St. Bernards still come in both smooth- and rough-coated varieties.

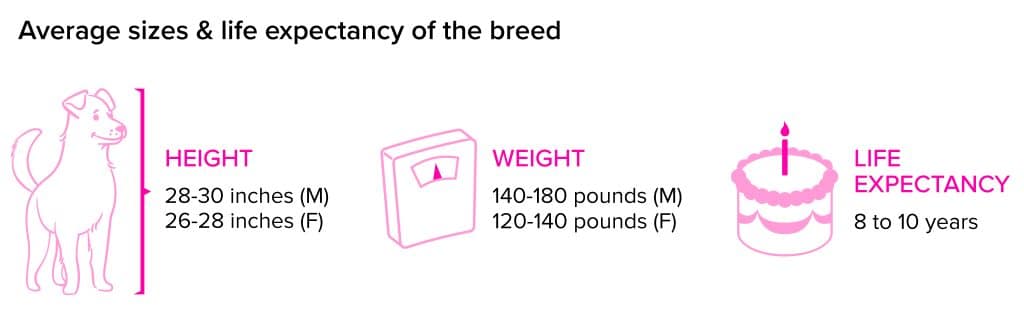

The American Kennel Club breed standard for the St. Bernard describes a powerful, muscular dog with a massive skull. The head in particular has been of great importance in this breed over the past century, and contemporary dogs have much larger heads and shorter, deeper muzzles than the old working dogs did. In colour they are white and red-brown, generally patched, with white blazes, chests and feet. Blackish face masks and ears are common. The rough- and smooth-coated standards are identical except for coat characteristics, and the types are occasionally interbred. Males must be a minimum of 27.5 inches at the shoulder.

The St. Bernard is known as a giant breed, and giant dogs have many potential health problems. First and foremost for many people is a relatively short life expectancy—eight to ten years is fairly normal. Of special concern also in the St. Bernard is soundness and ease of movement, especially of the hindquarters. The breed became very popular as a pet for a period, and began to display high rates of dysplasia. Even apart from genetic disorders, these dogs don’t fully mature until they are about three years of age and must not be exercised hard when young. There can be difficulties if young puppies are fed too rich a diet and grow too fast. If you want to own a St. Bernard, you must do your homework both before and after you buy. Number one is to find a reputable breeder. Ask lots of questions, and heed the advice.

Fotoskat/Bigstock

When my family had a St. Bernard in the mid-1970s, we were warned that individuals could be a bit “overprotective.” While the early dog was renowned for its steady, calm, amiable disposition and profound love for children, aggression became an issue as the breed gained popularity and began to show signs of inbreeding. One simply cannot afford to have a dog with a nasty temperament when it is the size of a St. Bernard! And given that these dogs are derived originally from mastiff-type stock, it is necessary not only to seek out a breeder who takes great care with disposition, but to spend the time needed to properly socialize the dog with both humans and other animals. All mastiff-based breeds are protective by nature and have the potential to misgauge a situation if not properly educated.

One thing you will be told over and over is that St. Bernards drool. Most do, quite copiously. They flip their heads and lines of slobber end up wrapped around their muzzles (or worse, hanging from your dish rack). This is a natural consequence of the head shape that show breeders have aimed for over the past century: The lips hang down. Most of us have experienced something akin to this in the dentist’s chair. Recently there has been talk of “dry-mouth” St. Bernards—ones that do not drool, or at least ones that drool less. This can be achieved by breeding for a longer, narrower muzzle. However the muzzle shape then tends to fall outside the current breed standard. Since pet-dog owners don’t necessarily care about breed standards and showing success, some breeders may be headed in this direction. If a breeder who is primarily concerned with soundness and temperament has also opted to go for “dry-mouth Saints,” by all means buy a dog from him or her. But it should never be your first consideration with a St. Bernard.

These dogs do shed, and they have lots of hair. On the other hand, they do not need special grooming procedures. Daily brushing and occasional baths are sufficient to maintain the coat.

The St. Bernard is a wonderful dog for the right household, particularly one with small children. As with all breeds, it has its pros and cons. As always, prospective owners must carefully consider their own lifestyle and preferences and what they are truly seeking in a dog (e.g., this is not a good companion for a long-distance runner). To be happy, a St. Bernard must have human companionship and guidance, firm training from an early age and, most importantly, it must be included as part of the family rather than left outside in the yard. But if quiet, steady, loyal and loving companionship is the wish—and the couch is not too tiny—a properly bred and well raised St. Bernard is an excellent friend and family dog.

» Read Your Breed For more breed profiles, go to moderndogmagazine.com/breeds

This article originally appeared in the award-winning Modern Dog magazine. Subscribe today!

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.