- Dog CareDog LifeCommunity

- Photo Contest

Photo Contest- Giveaways

Deaf Dogs Can Do It All

They say that close friends can comfortably share a silence. If so, Karlie Waldrip and Rhett are the truest and best of friends.

The 27-year-old Grapevine, TX resident and her Blue Heeler Australian Cattle Dog can enjoy a quiet night at home better than most—they’re both deaf and proud to be.

Waldrip believes that she and Rhett share a unique bond. Born with moderate to severe hearing loss, Waldrip was diagnosed as deaf at ten months old.

Doctors told her parents that, statistically, Waldrip would not learn to read past the third-grade level, and that they had to choose between teaching her sign language or teaching her to speak. The Franke family went to bat for their daughter, and with the help of a home advisor for the deaf and hard-of-hearing, schools that supported her educational needs, and many years of practice, Waldrip beat the odds. She became an exceptional reader, speaker, and is fluent in sign language and lip reading.

There were obstacles. “I felt so left out (of) conversations around me and could not hear certain sounds,” remembers the Austin, TX native. “I became so frustrated seeing people around me laughing, talking, joking, etc. because I could not understand anything unless I was talking one-on-one in a quiet place… I struggled with accepting my deafness when I was younger because I wanted to be ‘normal’ like my peers.”

Karlie Waldrip and RhettA cochlear implant—a surgically implanted hearing device that uses a microphone to bypass the hearing process and takes sounds directly to the auditory nerve—and a hearing aid, replaced by a second implant at the end of her high school years helped, but her hearing is not fixed, she said. “When I take off my ‘ears,’ I am completely deaf.”

She had always loved dogs (the Frankes had Papillions when she and her sister were growing up), but it was a deaf-education teacher who’d help cement that lifelong love.

“She had a therapy dog who was deaf,” remembers Waldrip. “She was a huge dog lover and would bring her dog to class every Friday. All of her students became dog lovers because of her.” The teacher incorporated dogs into her lesson plans and taught students how to approach, train, and care for them.

Waldrip not only accepted her identity as a deaf person, but became proud of it. After graduating from Texas State University and becoming an itinerant teacher for the deaf and hard-of-hearing—a job she is “forever thankful for because I get to work with students who have some sort of hearing loss,” she says—Waldrip planned to adopt a deaf dog.

“In some way I felt I could relate to them,” says Waldrip. “I knew there were so many dogs being overlooked just because they were deaf. I wanted to be that person who saw them and gave them the life they deserve.”

She adopted Rhett from a shelter in nearby Gonzalez, TX. “I fell in love with Rhett the second I saw him. He immediately jumped into my arms for a big ol’ hug and kiss then went down to the ground for belly scratches! I loved that he just came right into my arms, he was so comfortable with me.” Shelter staff described it as a match made in heaven.

“The only thing that is different is instead of using voice commands, you use made up hand signs or sign language. The key is to be consistent.”

As soon as Rhett arrived at his forever home, it was time to train. “I knew dogs who were deaf are visual due to my experience of being deaf, she said. “The only thing that is different is instead of using voice commands, you use made up hand signs or sign language. The key is to be consistent.”

First, Waldrip taught Rhett “thumbs up” meaning good boy/good job. “I did this sign every time he did something good with lots of body language of excitement and facial expressions. Dogs who are deaf are very visual so he knew he did something right. I was very consistent with it and he picked up on it really quickly.”

Next, was “check in.” Every time he looked at her, Waldrip gave him the thumbs up with body language, facial expressions, and treats. “This will help them to independently check in with the owner every few seconds in every situation they are in,” she says. “Touch is also critical, in my opinion, to reduce getting startled every time they are touched to get their attention. I would tap him gently, and when he looked, he got thumbs up and praise.” Rhett learned signs for different objects such as ‘car,’ ‘ball,’ ‘sit,’ ‘down,’ ‘dad,’ ‘mom,’ and ‘walk.’

“I would show him the object/thing, then show him the sign, then show the object again along with the sign, teaching him to connect the sign with the object,” she says.

She advises consistency and patience for those training any dog, hearing or not. “Every dog takes a great deal of patience. We all train/learn differently,” she says. “Learn signs or make them up, they work just the same… It is like learning another language—some pick up quickly, some don’t as quickly.”

Rhett“The challenges really lie with the people just becoming comfortable with using non-auditory communication,” says Terrie Hayward, a certified professional behaviour consultant and dog trainer at Positive Animal Wellness (positiveanimalwellness.com) specializing in non-auditory communication and dogs who suffer from separation anxiety. “Once folks understand how to consistently mark and reinforce behaviours they would like to see more of—as well as accurately interpreting, understanding, and responding to dog body language—communication can be smooth and effective.”

Caribbean-based Hayward—who also has two deaf dogs of her own—is the author of the book, A Deaf Dog Joins the Family: Training, Education, and Communication for a Smooth Transition. She has also done webinars on visual, tactile, and non-auditory communication with deaf dogs and runs a Facebook group called Deaf Dogs Behavior and Training.

Information on deaf dogs is out there in abundance, says Waldrip. “I like joining Facebook groups for dogs who are deaf; they all come together to support and share experiences,” she says.

Rhett, now three, and his mistress are inseparable. “He is my best friend and my shadow,” she says. “It sounds cheesy, but we understand each other. We show the world our abilities and how smart dogs who are deaf truly are.”

She may have rescued him, but he’s supported her in equal measure. When the pair relocated for Waldrip’s new teaching position, he was a magnet for new friends. “People are always stopping to meet us since he wears his ‘deaf dog’ harness and has unique coating for a Cattle Dog.” It seems Rhett has star quality. He won a photoshoot and the pictures the photographer posted on Facebook went viral. In a lightbulb moment, Waldrip made Rhett an Instagram account—@_rhett_the_heeler has more than 17,000 followers—with a mission of educating others about deafness in dogs.

“The fact that we are both deaf is a unique factor that pulls in dog lovers and people in the deaf community,” Waldrip says. She wants people to know that if they fall in love with a dog, deafness should never be a dealbreaker. “Deafness does not define who the dog is or their abilities.”

“Deaf dogs can do everything their hearing counterparts can,” seconds Hayward. “Really, the learning curve is for the humans—in working on understanding how to effectively communicate via visual and/or tactile cues.” These cues can even be taught to dogs that aren’t deaf, Hayward says. “It’s a good idea to begin adding visual or tactile cues to your (and your dog’s) repertoire so that if your dog loses their hearing, you have already begun with some communication tools.”

While deafness affects dogs of all breeds in old age, it is more common in certain breeds such as Dalmatians, Boxers, and Australian Cattle Dogs, says Hayward.

Patricia Belt, an advocate for dogs who were born deaf, has four deaf Dalmatians—Izzy, 10; Astro, six; Ember, four; and Piper, seven months—and a hearing cat named Dutchess in her family.

The Memphis, TN resident founded TN Safety Spotters Inc., a non-profit organization to help rescue deaf Dalmatians, train them, and “set an example of the amazing things deaf Dalmatians are capable of, if given a chance.” Belt and her dogs are fire prevention educators at the Fire Museum of Memphis, work with veterans who have mobility issues at the Memphis VA Medical Center, and do therapy visits at fire stations.

“They make wonderful therapy dogs because they rely on body language and facial expressions to communicate,” says Belt. “They know who needs them the most and will naturally visit them first. Deaf dogs hear, just not with their ears.” Her dogs are also reading education assistant dogs. “Children who have reading difficulties relax reading to a dog, knowing the dog won’t laugh at them when or if they make a mistake,” she says.

When they aren’t working, they’re enjoying happy lives as regular dogs. “I let home be a place where they can relax and feel free to run and be carefree dogs,” says Belt. “They sleep on the couch, play ball, and run in the backyard like any dogs.” They also play nose-work games since they have a keen sense of smell. “There is never a dull moment.”

“If you are willing to commit to one, your life will never be the same,” says Belt of deaf dogs. “You’ll have the best friend you’ve ever had. They will understand your moods and be there for you through good times and bad… The bond you will have with your dog will be closer than you will ever imagine.”

As for Rhett, “he is deaf and the happiest dog he could ever be,” says Waldrip. “He is living the best life with me. I have given Rhett a voice to educate others about dogs who are deaf in hopes of giving other deaf dogs a chance.”

Answers to the Most Commonly Googled Questions About Deaf Dogs

Dog trainer, deaf dog advocate, and therapy dog evaluator Patricia Belt answers the most commonly Googled questions about deaf dogs.

Q: How do you call a deaf dog?

A: I first teach deaf dogs to check in with me every 30 seconds or so. When they're looking, I give the “come” hand signal. If they're focused on something very distracting and check in, I use hand targeting. I always have something of higher value (better than what they are focused on) and worth coming for. If it's at night, I turn the back porch light on and off. They know to come.

Q: How do you wake a deaf dog?

A: Whether hearing or deaf, you must be careful waking a dog. When training, I tap on their shoulder to wake them up and offer them a high-value treat or game. They learn waking up suddenly means good things are coming. If the dog is known to nip or bite when waking, I lightly stomp on the floor a few steps away. Once they're awake I'll toss them a few treats.

Q: How do you get a deaf dog's attention?

A: When training, teaching “watch” is the very first exercise. If they don't know to “watch,” they can't read hand cues or body language. Every time the dog makes eye contact, I reinforce with a delicious treat. When trained, I can tap on their shoulder, and they turn and look at me. I always have a big smile and thumbs up waiting! Once they learn to watch, getting their attention is not a problem. I never have my dogs off leash unless it's in a fenced, secure area, no matter how well trained they are.

Q: How do you prevent startling a deaf dog?

A: With hearing or deaf dogs, startling can and does occur; it's instinctive. It's how they react that's important for our safety. Training a deaf dog with gentle taps from behind and reinforcing good behaviour and being able to keep triggers or surprises to a minimum helps teach them to react in a positive way.

Two-Year-Old Adopts Shelter Dog With Same Birth Defect: “They instantly loved each other”

When Brandon and Ashley Boyers discovered Lacey, a black and white puppy with a congenital birth defect, at the Jackson County Animal Shelter in Jackson, MI, they knew she would be the perfect companion for their two-year-old son, Bentley. Like their toddler, the puppy had been born with a cleft lip.

Brandon was visiting the shelter when he realized one of the puppies had something in common with his son.

“He Facetimed me. He goes, ‘I think this one has a cleft lip’ and I said, ‘get her! We need her,’” Ashley told local news station WILX.

When the overjoyed toddler visited the shelter to meet Lacey for the first time, the team was able to capture an adorable series of photos highlighting the instant bond shared between the boy and his new puppy.

“It’s so hard to put into words how meaningful this adoption is to all of us so we are going to let the pictures speak for themselves,” the shelter said in a Facebook post. “…They instantly loved each other.”

Being able to see yourself reflected in the world around you is so important. “To see him have something in common with a puppy means a lot ’cause he can grow up and understand that he and his puppy both have something that they can share,” Ashley said.

Lydia Sattler, the Jackson County Animal Services Director, noted that Lacey should not have any additional health issues.

“Her disability is really not holding her back, and as she grows, they’ll be able to see more if there’s any change that has to do with that. But she’s really doing well,” Lydia told WILX. “She might look a little different than a normal dog would, but it’s not slowing her down at all.”

Land of the Strays

Volunteer José Rojas shares a quiet moment with his beloved dog Franco, who suffers from narcolepsy, as rain clouds begin to roll in during the late morning. Photo by Dan GiannopoulosDeep in the fertile mountains near Heredia in Costa Rica, about an hour outside of San José, lies a 350-acre farm and sanctuary known as Territorio de Zaguates. Frequent rainfall feeds the lush green rolling hills and crystal-clear streams. The landowners allow for the natural trees and landscape to grow in, a wild contrast to the many nearby farms that clear-cut for cattle ranching.

Animals do run through the fields of this farm, but they are not of the livestock variety—they are dogs. Over 2,000 of them.

Owner Lya Battle inherited the farm from her father—it was originally owned by her grandfather, who selected his property based on its picturesque view. She simply did not know what to do with it before opening up the Territorio de Zaguates dog sanctuary and shelter about a decade ago. Today, she runs the operation along with her husband, Alvaro Saumet, and five full-time caretakers looking after more than 2,000 dogs. “Imagine this,” Lya says, setting the scene over the phone from Costa Rica. “Each day, we open the dog enclosures and let the dogs roam free. We take them for a four-kilometre walk up and down pastures, they run through rivers, roll in the grass, chase birds… It is pretty similar to paradise. Especially because it is full of dogs.”

The dogs rest before making their way back down to the main farm area for feeding time. Photo by Dan GiannopoulosDespite being a lifelong animal lover, Lya spent her early years unaware of just how bad the stray situation was in San José. That changed when she moved to a suburban neighbourhood with her husband almost 15 years ago, and she encountered many more strays—as well as one particularly beautiful dog with an eye problem. “Imagine a handsome Husky, but with two shades of yellow, and probably mixed with a Shar Pei because he had these little triangular-shaped ears,” she recalls. Lya was smitten; she took the stray to a vet to get his eyes fixed, expecting to find an owner for him after the fact. “That was the first time I thought of holding on to a dog until someone wanted him, which ended up being his entire life, because nobody ever did.”

Naming the dog Oso (Bear in Spanish), the golden-hued canine marked the beginning of a life’s mission that has grown far beyond what Lya ever anticipated. “I realized there are a lot of dogs out there who don’t have a home, and there simply wasn’t an option for them,” she says. “They are either risking their lives on the street, or they are waiting for their due date [to be euthanized] in a shelter. That’s it. And that became a haunting feeling for me.”

José Soto, a local caretaker, sits with the dogs during a rest break on their daily walk. Photo by Dan GiannopoulosOne by one, she added to her count of rescues, but when the tally reached over 100, moving them to the farm was the natural next step despite some naysayers who didn’t believe large packs of dogs could co-exist in harmony. Quite the opposite, Lya’s rag-tag clan of strays was happy to live as a herd, and she noticed behaviourally how the new dogs were taught by the old guard. (It also helps that all the dogs are spayed and neutered.)

At Territorio de Zaguates, each dog is a member of the greater family, and each dog is given its own name. A large part of Lya’s operation is adopting them out to welcoming homes, not only in Central America, but to the United States and Canada, too. Prospective families are carefully screened in advance, but even then, the dogs can be returned to the farm if there are any issues. “I always tell people, ‘There is no expiry date on this adoption.’ We won’t even ask questions,” says Lya. “If you can’t have them anymore, for whatever reason, bring them back.” While it is sad to see a dog returned, there is deep reassurance for Lya knowing that they are safe.

About 15 years ago, adopting dogs was virtually unheard of in Costa Rica; Lya explains how there is still so much education that needs to take place—not only about adoption, but caring properly for pets in general “People always want puppies, too, so we have to educate them on adopting adults,” she adds. These days, new dogs generally join the sanctuary as a result of tips that they receive about abandoned dogs. While adoption numbers move faster than they used to, they could always be quicker.

Territorio de Zaguates dog sanctuary founders Lya Battle and husband Alvaro Saumet. Photo by Paola Bonilla Fong (IG: ppunto.photo)Running the operation not only takes a lot of heart, but a lot of funding. Lya and her husband do not make a profit from the shelter and work separate jobs in order to keep it afloat. (Four days a week, she works as an educational consultant; Friday is dedicated to running around on the farm.) Donations help, too. The sanctuary has a robust online presence and donation platform and the local vets who allow the organization to keep running tabs. The weekly dog food bill—they go through 20 sacks of kibbles daily, each weighing 30 kilograms—is also incredibly high. But for Lya, it is all worth it: “I never really intended to do this. I just realized that the existing reality was not something I was comfortable with, and I tried something different because it was the least I could do. And I’m still trying.”

“The dogs roam free… they run through rivers, roll in the grass, chase birds…It is pretty similar to paradise. Especially because it is full of dogs.”

Trying is an apt descriptor for other reasons, too. Of the daily challenges Lya and Alvaro face, the biggest of them all is working through the hoops of government regulation, at all levels. “Our government is not going to help a dog on the street. We don’t even have municipal pounds,” Battle says. “But then the government wants us to build our shelter their way? Keeping all the dogs in cages, for example? No. This is my property. So, they’ve tried to come up with as many challenges and problems that they can put in our way.” Although she says they have been demonized because they are doing something different, Lya, true to her last name, keeps fighting. For her, it is better than the alternative. “It has almost become like a tug of war for us and the government, which we usually end up winning every time because, really, how can you deny that what we are doing is working? It’s working.” The proof, for her, is in the happiness of the dogs, living in the verdant hills with kind caretakers and enough food, free from stress and trauma.

Photo by Diana Méndez Arias (IG: dimearias). Founder Lya Battle hugs one of the sanctuary dogs. Photo by Paola Bonilla Fong (IG: ppunto.photo)“I sometimes tell people ‘I have a farm full of walking deads’—that is, dogs that would have been euthanized but are there because they had a chance.” Even though some of the sanctuary’s inhabitants are on their last legs—are elderly, or have cancer, for example—they will at least will leave this earth from a loving environment. One dog, named Abuelo (which means Grandfather in Spanish) came at the age of 12 after his owner passed away. Not only did he live to be age 21 at the shelter, but after a video of his birthday party was shared on the shelter’s social media account, he got adopted. Still alive and living with his new family, he is now almost 24 years old. Today, Abuelo lives like a prince in a large house with multiple doggy beds and a pool he likes to lay beside. “These are the stories that keep me going,” says Lya. “Nothing is more fulfilling than that, nothing can take up more of my heart than that.”

With visitors to the sanctuary suspended first due to construction, then due to Covid-19, the educational group walks with visitors have been put on hold, although there are hopes to start them up again in the new year. “That was our way of teaching 300 people in a weekend about how to care for dogs,” she says, “and getting a whole bunch of dogs adopted in the process.”

José Rojas, a volunteer from Costa Rica, and Darlin, a senior caretaker from Nicaragua, supervise the dogs during their daily walk. Photo by Dan GiannopoulosStill, Lya remains hopeful, and the land of the strays, as many call the farm, remains vibrant. “I think only Costa Ricans call their mutts zaguates,” says Lya referencing their name, explaining that the word is taken from the Bri-bri language of Costa Rica’s Indigenous people from Talamanca. “When I gave our farm its name, people questioned it, but you know what I said to them? ‘There is absolutely no shame in being a dog who doesn’t have a breed. A zaguate is a survivor. A zaguate does not come from the prettiest dog made to mate with the other prettiest dog. No, it is a survivor with a survivor. If there is anything like a superhero, and a warrior, it is a zaguate. It is a dog that made it, against all odds.”

The dogs run excitedly across a hilltop just behind the main farm under the watch of Alex, a caretaker at the farm. Photo by Dan GiannopoulosMeet Mr. Breakfast

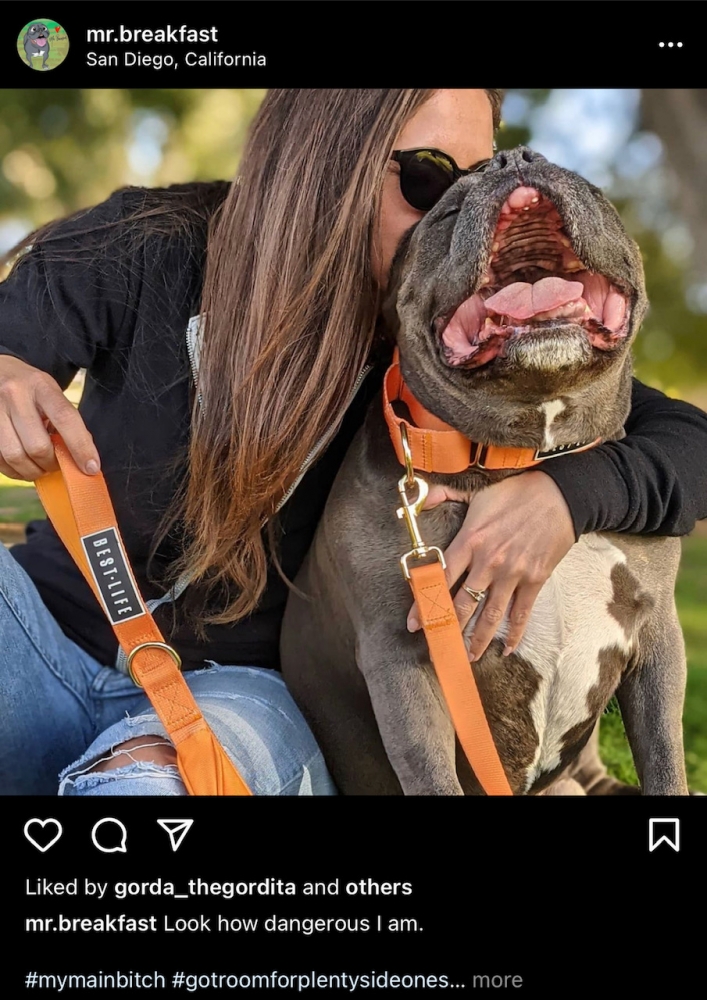

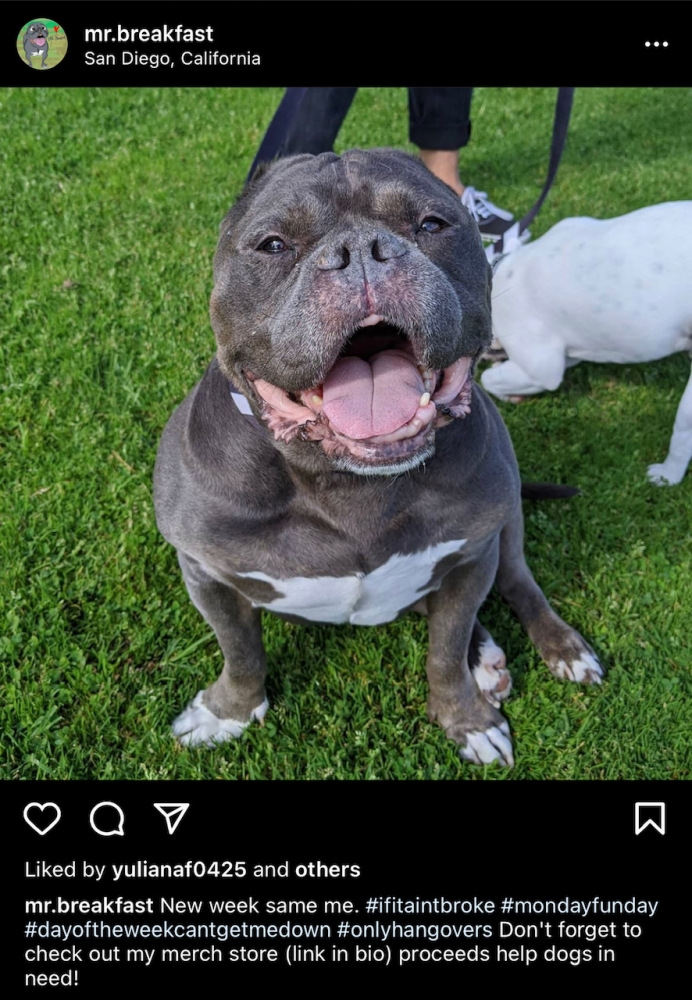

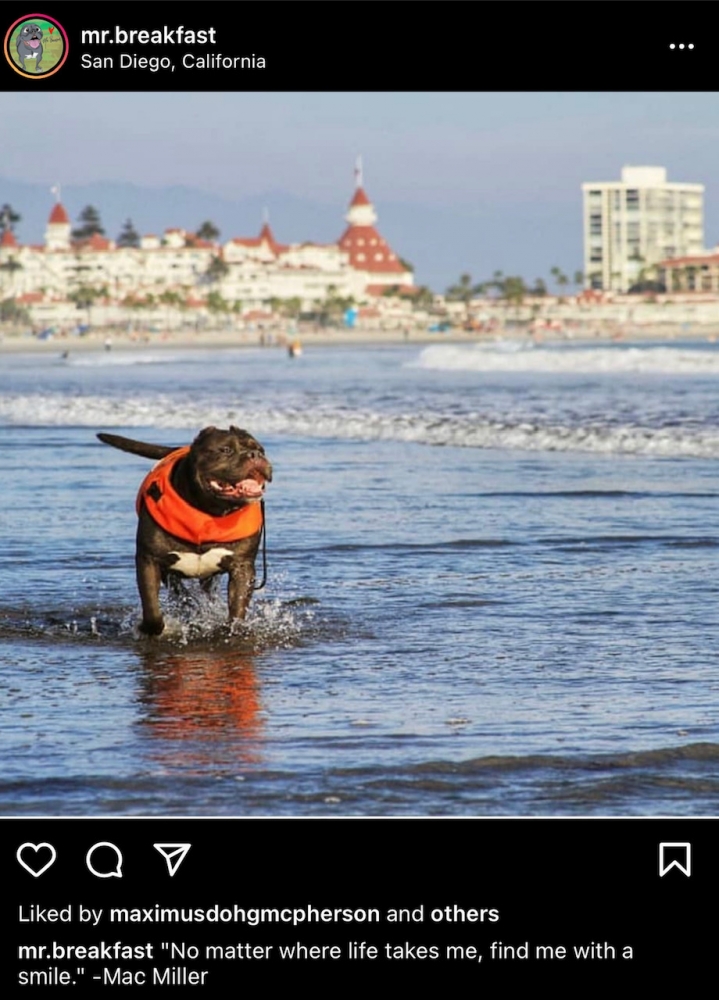

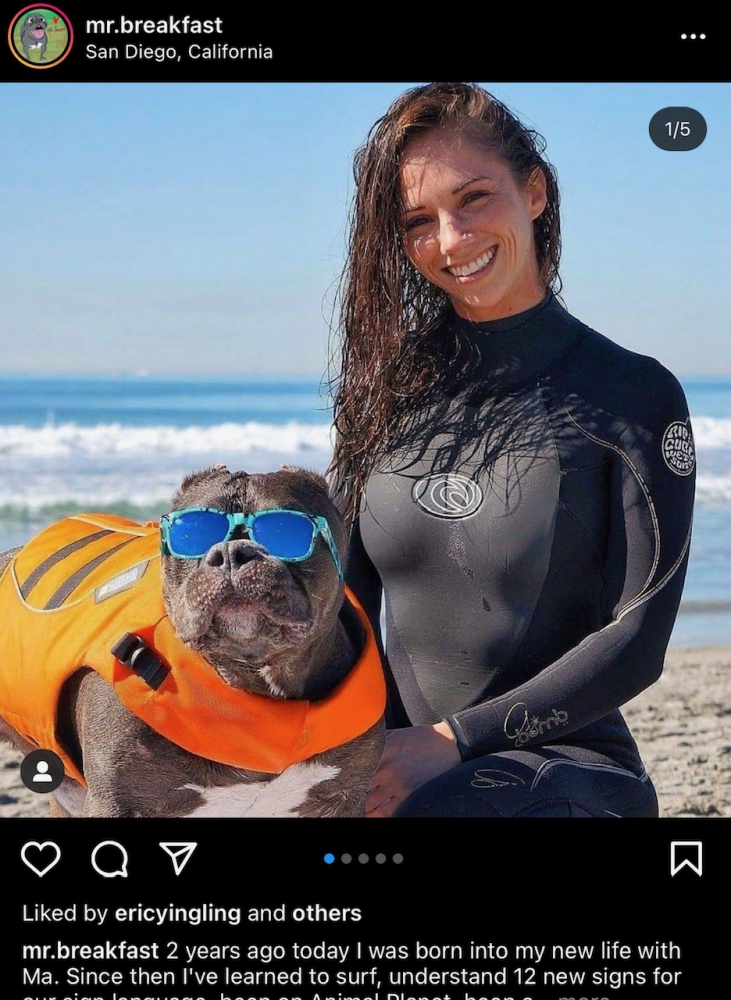

The cards were definitely stacked against Mr. Breakfast, who was rescued from a dog fighting ring in San Diego, CA, and was almost completely deaf due to the close cropping of his ears and subsequent infections. With a couple failed adoptions behind him, no one could have guessed this fierce-looking, unwanted dog would turn out to be a sweetheart with a passion for surfing.

Mr. B’s life changed when he found a forever home with Liz Nowell. Not trained to be a pet, he came with behavioural issues, but Liz, having worked with deaf dogs before, was up for the challenge.

With Liz, Mr. B learned sign language and developed an affinity for surfing, an activity that bolstered his confidence and strengthened their bond. The duo has fond memories of hanging ten at dog surf camp.

Having a deaf dog comes with unique challenges, mainly the need for a lot of patience. “It’s easy to get frustrated when he looks away from me and misses a sign, or when he gets into something and I have to get up, stop what I’m doing to tap him and redirect his attention,” Liz said on Instagram. Otherwise, she says having a deaf dog is not much different than having a hearing dog that just doesn’t listen. Most of all, she stresses patience and professional training.

Though his look might be a little intimidating, Mr. Breakfast is a softie at heart. He grumbles like an old man and makes “happy hippo noises” while enjoying scritches. Strangers comment on his happy-go-lucky nature. And he loves food—especially breakfast.

Thanks to Liz, Mr. Breakfast finally found the love he deserves, as well as over 33k adoring followers on Instagram.—Becky Belzile

Dogify Your Inbox

Sign up for the FREE Modern Dog Magazine newsletter & get the best of Modern Dog delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.