Rescuing Wolfdogs

Get to know these amazing, mysterious creatures

Wolves have a special place in our imagination: mysterious, charismatic, and highly intelligent, they represent all that is beautiful about the wild. It is easy to understand why people are enchanted with wolves and how this could carry over to the desire to own a wolfdog, the hybrid result of the mating of a wolf and a dog. It is a chance to connect with what is wild in nature, and for some, a chance to connect with their own inner wolf. However, many people, lacking an understanding of the special needs of these magnificent animals, find themselves unable to handle them; the unfortunate result is that wolfdogs often end up abandoned and abused. “Sadly, the majority of them are euthanized by the ages of two or three, when they reach sexual maturity,” says Wolf Haven International, a wolf sanctuary based in the U.S.

In Canada, Yamnuska Wolfdog Sanctuary (YWS) rescues displaced wolfdogs, providing a permanent sanctuary for some and finding homes for others. Located on 160 acres of land in a quiet, rural setting about half an hour west of Calgary, AB, the sanctuary is the permanent home of several resident wolfdogs, as well as a number of adoptable ones.

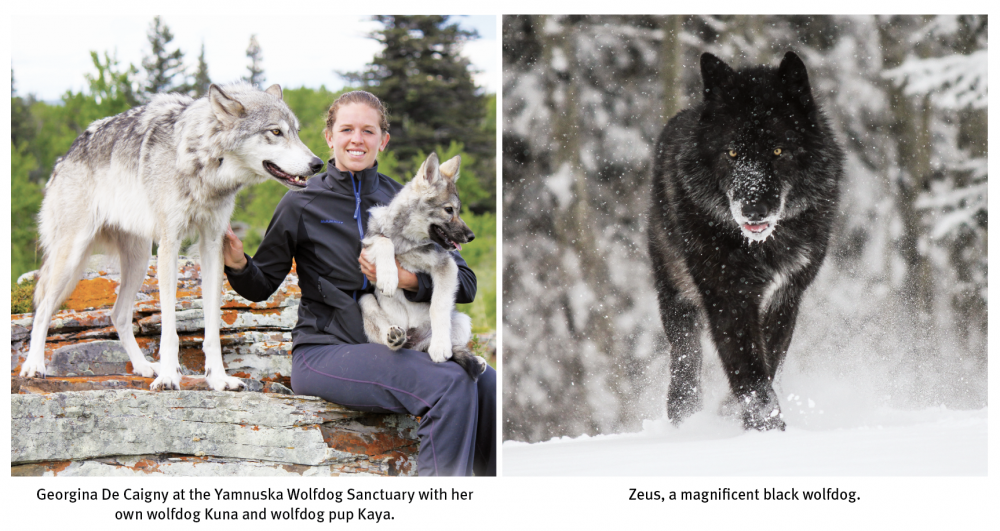

“While domestic dogs are programmed to please people, Kuna was different,” says De Caigny. “She was smart, stubborn, and incredibly independent, and she had no need for someone else to provide her with leadership.” De Caigny describes their relationship as a journey the two of them took together, learning about the other species. “In the end, Kuna made a choice. She chose to love me, and she chose to be with me, and that is why I love her so much.”

Scheibenstock went on a similar journey of discovery when De Caigny introduced her to Artimus, a part wolf, part Malamute dog, who had spent her life on the end of a large, heavy chain. “I adopted her and love her to pieces,” explains Scheibenstock.

Aside from providing a refuge for displaced wolfdogs and finding homes for those suitable for adoption, YWS gives visitors a chance to meet wolfdogs up-close and learn more about these fascinating animals, who are often misrepresented and misunderstood. “I wanted to stand up for wolfdogs and dispel the many myths about them,” emphasizes De Caigny. Scheibenstock, who is presently working as a physician in Cranbrook, BC, is in touch with the sanctuary on a regular basis. She looks forward to the day when she can be there permanently. “When I retire—hopefully sooner than later—I hope to use all my energy to rescue many more wolfdogs and be there full time,” Scheibenstock explains.

Although many scientists believe all dogs originally descended from wolves over hundreds of generations, wolfdogs have wolf closer in their genetic makeup. Most wolfdogs today are not created at random by a pure wolf in the wild mating with a domestic dog; rather, they are the result of breeding by people. What they are like depends largely on the amount of wolf in them. The more generations they are away from the original wolf parent, the further they are from having wolf characteristics. At YWS, Nova, a beautiful white wolfdog born in a breeding facility in the United States, is an example of a wolfdog with substantial wolf in his makeup.

Since a wolfdog is part dog, its character also depends on the breed of dog in the mix. Most often, wolfdogs are bred with northern breeds such as the Siberian Husky and Alaskan Malamute, which already have a “wolfy” look. However, there can be tremendous variation in any litter of wolfdogs, with some having more wolf characteristics and others having more dog traits. Genes are selected from both parents but this occurs randomly; which genes will be selected cannot be predicted.

Temperament also depends on their upbringing and individual personalities. Pointing to Zeus, a magnificent black wolfdog, De Caigny notes he has a strong aversion to entering small spaces. Even with food as enticement, Zeus cannot be persuaded to enter. Kaida, on the other hand, is more motivated by food than a fear of restricted areas and will enter a small place when delectable delights are put there as encouragement.

Since dogs likely descended from wolves, and some dogs such as the northern breeds look very wolf- like, how can you tell if a certain animal is just a dog or actually a wolfdog? Moreover, if it is a wolfdog, how much wolf is in it? Since there aren’t any genetic tests that reliably prove how much wolf is in an animal, experts use a process called phenotyping, which is a means of arriving at an educated guess about an animal’s heritage based on appearance and behaviour. In general, wolfdogs are classified into three categories: high-content, mid-content, and low-content.

A high-content wolfdog acts more like a wolf than a dog; it is often described as curious, cautious, highly intelligent, and aloof. Although some believe wolves are aggressive and confrontational, that is not true: like wolves, a high-content wolfdog will normally be shy and retreat from humans. People who acquire a high-content wolfdog thinking it will make a good guard dog are bound for disappointment. Instead of challenging a stranger, it will more likely cower and back away.

Similar to a wolf who roams over large distances in search of food and shelter, a high-content wolfdog will more likely wander than settle. Providing adequate containment for one of these animals entails having a large enclosure with an eight to ten foot fence as well as dig guards and an overhang. Experts recommend using a heavy, nine-gauge chain link since wolfdogs have been known to chew through seven-gauge. In addition, they need plenty of exercise: a daily walk on leash, which is sufficient for many domestic dogs, is vastly inadequate for a wolfdog.

A wolf in the wild is often thought of as being solitary, hence the expression “lone wolf.” This is another misconception. Wolves are highly social; they live in a pack and thrive on the strong bonds created with their pack members. This means a high-content wolfdog should not be left alone; wolfdogs need at least one other canine companion.

A high-content wolfdog acts more like a wolf than a dog; they are often described as curious, cautious, highly intelligent, and aloof.

“A high-content wolfdog is not like a typical pet,” explains De Caigny. “It exhibits far more pure wolf characteristics and does not belong in a private home.” She adds that Nova, Zeus, and Kuna are all high-content wolfdogs and so “they have a permanent home at this sanctuary; they will never be adopted out.”

As the name implies, a mid-content wolfdog has characteristics that are about half wolf and half dog, while a low-content wolfdog generally exhibits more dog traits than wolf. Being more like a domestic dog, low-content wolfdogs are more willing to please, are generally easier to train, and are the ones most suitable for adoption in private homes. Even so, a potential owner must be an experienced dog handler as well as knowledgeable about the special challenges of raising wolfdogs. “I want people to have the right expectations and know what they are getting into,” explains De Caigny.

She recommends that potential owners learn about wolfdogs by volunteering at a rescue centre or by fostering an animal. While YWS is the only refuge in Canada, there are several rescue organizations in the U.S. including the Florida Lupine Association, Howling Woods Farm, and W.O.L.F. (Wolves Offered Life and Friendship). These organizations provide extensive information about what is involved in wolfdog ownership. In addition, there are several books available such as Living with Wolfdogs: An Everyday Guide to a Lifetime Companionship, and Hit by a Flying Wolf: True Tales of Rescue, Rehabilitation and Real Life with Dogs and Wolves written by Nicole Wilde, a nationally recognized dog trainer, wolfdog expert, and Modern Dog regular contributor. These books provide practical information about how to raise a wolfdog. Wilde, who promotes responsible wolfdog ownership through education, provides this advice for potential owners:

- Before you even consider a wolfdog, find out what the legalities are in your area.

- Consider whether you can provide the proper containment; a 6 foot high fence is no challenge for these escape artists.

- Although wolfdogs can be sweet and affectionate, they are a lot of “dog.” Experience a Siberian Husky first to see whether that personality type (and then some!) is what you really want.

- Do plenty of research before jumping in, because wolfdog rescues are perpetually full and unwanted wolfdogs often end up euthanized by shelters.”

As Wilde notes above, laws regarding wolfdog ownership vary throughout North America. In Canada, it is currently legal in the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan but illegal in Manitoba and Eastern Canada. In the United States, wolfdog ownership is legal in about a dozen states although some places require special permits or enclosures.

Why are wolfdogs legal in some areas and not in others? Advocates use adjectives such as intelligent, playful, curious, and independent to describe them. They say these beautiful animals are exceptionally loving and loyal to their family pack and owners can form a much deeper bond with wolfdogs than with domestic dogs. Opponents say wolfdogs are unpredictable. While domestic dogs have been bred over generations to produce dependable behaviour traits such as those found in herding, guardian or companion dogs, opponents posit that wolfdogs are mutts and their behaviour is inconsistent. They argue wolves are wild animals and therefore wolfdogs are not appropriate as pets, further arguing that breeding a wolfdog is a disservice to both wild wolves and domestic dogs. And wolf rescue organizations fear that bad press about wolfdogs will taint the public’s perception of wolves in the wild.

Some animal professionals say wolfdog ownership should be banned while others argue that laws should target the breeders. Monty Sloan, a wolf expert and educator with Wolf Park, a wildlife research and education facility in the U.S., says, “Regulation should not focus on the banning of ownership of these animals but should direct its power to the underlying problem of the breeding and sales by individuals who produce far more pups than could ever be placed in ‘good’ homes.”

Although ethical wolfdog breeders can be found throughout the U.S. and Canada, there are plenty of unethical ones who capitalize on the public’s fascination with the animals. For example, in Alberta, Canada, YWS rescued several wolfdogs from a breeder who kept them in a small area between his house and garage and accessed the area by using a ladder to climb over a fence panel. “This clearly showed us these animals never got to come out of the enclosure and were rarely handled,” explains De Caigny. One of the animals, a beautiful white wolfdog named Seiko, had a noticeable eye infection. When she took him to the vet for treatment, De Caigny learned the infection could have been treated in its early days by using an inexpensive ointment. Since the breeder had failed to give Seiko proper veterinary care, the infection had gotten worse, and the vet had to remove the eye.

YWS notes that this breeder, while selling the wolfdogs for over $1000 each, misrepresented them as high-content wolfdogs when they were actually low-content, and failed to educate potential buyers about the challenges of wolfdog ownership. Sadly, stories like this are played out daily across North America. Even worse, many of these unethical breeders are still in business due to ineffective laws governing the proper care of animals. They continue to produce litter after litter of poorly treated wolfdogs, many of whom end up neglected or abused.

These beautiful animals—mysterious, misrepresented, and often misunderstood—clearly need someone to stand up for them. With the dedication of organizations like YWS—helmed by people who are passionate about wolfdogs—we’ve at least made a start.

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.