Why Doesn’t My Dog Like Other Dogs?

Understanding and addressing why your dog doesn’t like other dogs

If your dog lunges and barks at other dogs on walks or just doesn’t seem to appreciate the company of those of his kind, you’ve probably wondered why. Though it might be impossible to definitively ascertain the underlying cause, especially if your dog was adopted as an adult, usually one—or more—of the following issues is at play.

Breed

Every dog breed has a breed standard that states the ideal physical characteristics and describes the general temperament for the breed. This description can tell us a lot about how a dog of that breed might interact with other dogs. Part of the official AKC standard for the Akita, for example, states, “Akitas may be intolerant of other dogs, particularly of the same sex.” The Siberian Husky’s standard, on the other hand, includes, “…nor is he overly suspicious of strangers or aggressive with other dogs.” This makes sense, as Huskies were bred to work together in groups, whereas Akitas originated as hunting and fighting dogs. Of course, even within a breed there are dogs of varying temperaments—not all Akitas are dog-reactive, nor are all Huskies dog-friendly. But understanding the typical personality of your dog’s breed or breed mix can provide clues about their attitude toward other dogs.

Photo Tom Harper/ shutterstock

Socialization

Early, careful exposure to other dogs—or the lack of it—can play a huge role in how friendly a puppy will be toward other dogs later in life. A pup who has had plenty of positive interactions with other dogs during the first three months of life is much less likely to become dog-reactive or dog-aggressive as an adolescent or adult than a dog who did not have the benefit of early socialization.

Traditionally, puppy owners were advised to keep their pups away from others until the age of four months when all vaccinations were complete. But the American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior (AVSAB) now acknowledges that although puppy immune systems are still developing during the early months of life, “the combination of maternal immunity, primary vaccination, and appropriate care makes the risk of infection relatively small compared to the chance of death from a behaviour problem.” Accordingly, they now advise that puppies can start socialization classes as early as seven to eight weeks of age. In other words, the risk of physical illness from exposure is outweighed by the benefits early socialization conveys. Think of it as giving your puppy a dose of preventive behavioural immunity! Beyond meet and greets, you can also introduce your puppy to carefully chosen play partners. When introducing your puppy to another dog, always meet on neutral territory, avoid tension on the leash, and monitor the body language of both dogs carefully.

Trauma

Just like people, dogs can have lasting trauma after a frightening incident. A dog who was attacked by another dog could develop fear-based reactivity toward that type of dog, or toward other dogs in general. Even a dog who loves to play with other dogs could become dog-reactive after being attacked at the dog park. This is one reason it is imperative to use caution when choosing how to expose your dog to others. Exposing your puppy or adult dog to others via carefully managed one-on-one play dates is safer than visiting an unregulated dog park. If your puppy does have an unpleasant interaction with another dog,

Physical Issues

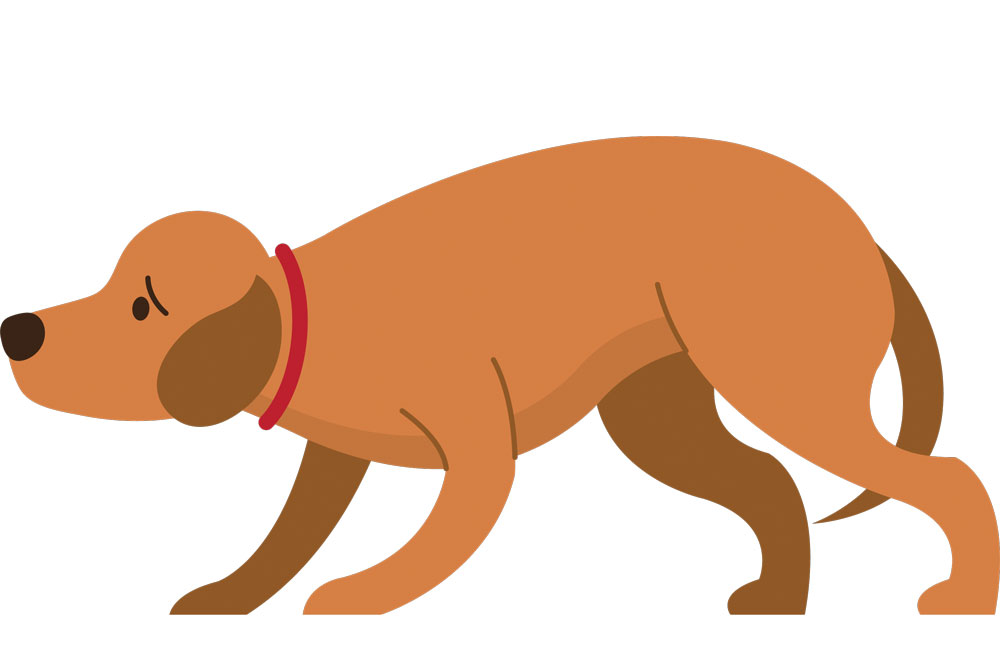

Physical or medical issues can play a part in how a dog reacts to others. An older dog who has arthritis pain in the hips, for example, is not likely to appreciate being hip-checked during play. A dog who has vision impairment may not see other dogs coming until they are at close range, and become startled and reactive. A dog who has any sort of ongoing medical issue where he does not feel his best may not appreciate the company of other dogs as much as a healthier dog might.

Predation

If your dog is only reactive to small dogs, the behaviour may not be true reactivity, but, rather, what is known as predatory aggression. The term is actually a misnomer, as there is no aggression involved in predation. A dog who chases a bunny is not angry with the poor rabbit, but is simply following his genetic programming.

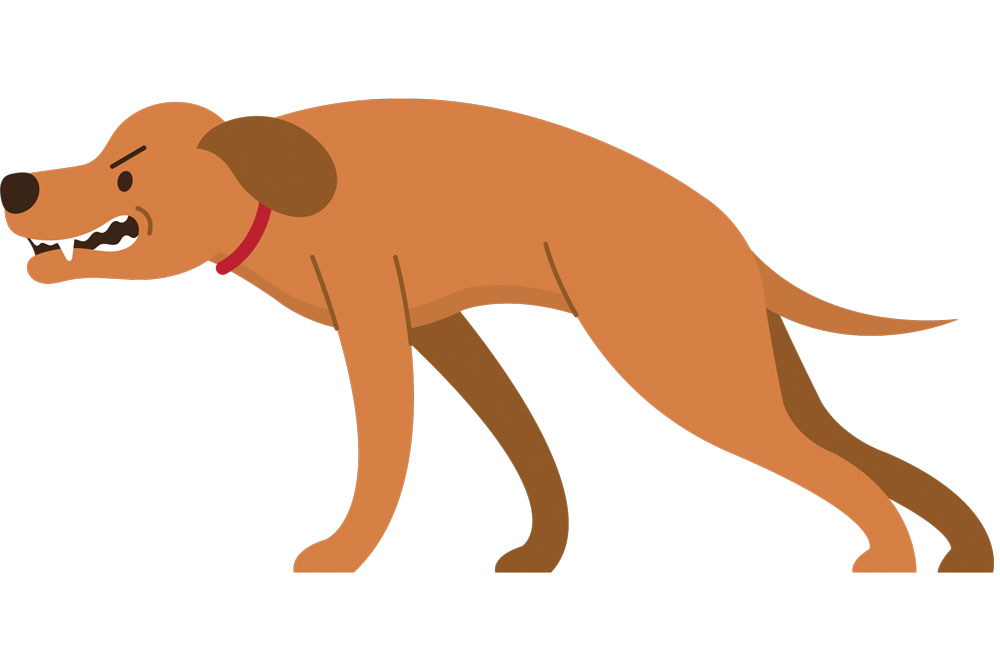

Leash Frustration

Some dogs are friendly toward other dogs and even enjoy playing with them, but once leashed, they lunge and bark at dogs who pass by. This is known as leash frustration. A leash prevents a dog from getting where he wants to go, which can be especially frustrating for dogs who have a low frustration tolerance. A leash also prevents a dog from escaping, so a fear-reactive dog may feel he has no other choice but to defend himself by driving the other dog away. In addition, when dogs are at liberty, they normally approach each other in an arc rather than head on, and then sniff to check each other out. A dog who is leashed is prevented from doing so. On-leash greetings usually begin with a direct, head-on approach, which can appear threatening. Solving dog-dog reactivity is explained in depth in my book Help for Your Dog-Reactive Dog but in a nutshell, the solution involves a combination of management, training, and behaviour modification. For behaviour modification, you might start with a handful of super tasty treats at a distance at which your dog is comfortable. Start feeding treats as soon as your dog sees the other dog. When the dog disappears, so do the treats. Dogs must learn that other dogs are nothing to fear and therefore nothing to react toward, while also learning acceptable alternative behaviours to lunging and barking.

The good news is that regardless of why your dog doesn’t like other dogs, dog-reactive behaviour is usually fear-based, and with the proper training and behaviour modification, can be helped.

This article originally appeared in the award-winning Modern Dog magazine. Subscribe today!

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.