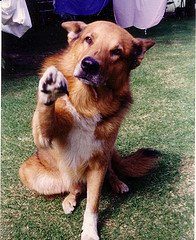

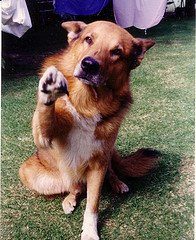

Why Do Dogs Give Paw?

From a Question and Answer Web Site:

"We used to have a Golden Retriever that would sit down and just look at us and give us his front paw. We always thought it was like him saying "please pet me." I tried to look online to see what this means but was unsuccessful. Do any of you guys know what this means?"

Best Answer – Chosen by Asker

In my house it means…

"Walk me……NOW"

"Dinner time, Lady… get up and make it happen"

"See these ears? they don’t scratch themselves"

"Did I mention I want a walk…because I do"

" Your ice cream….hand it over."

"Overall, it means they want attention of some kind."

Many say that dogs use their body language in place of verbal language as if a dog is thinking: "If I do this, then my human will notice me and then do that." However I resist this interpretation because it’s saying that dogs think just like we do, they just can’t talk about it. And it doesn’t diminish a dog to say its mind doesn’t function exactly as ours does. Rather I believe the mind of an animal is fundamentally different from the intellectual mind of a human because the latter is predicated on the concept of Time. Also, we recognize that the basis of body language is involuntary and can operate far below the cognitive plane and so simply attaching thoughts to the behavior shouldn’t satisfy our curiosity about its originating nature. So I suggest we return to the root of the behavior, the emotion, which I argue is a "force" of attraction, and then the subsequent feeling which arises from this as the basis of action. So putting the attention-soliciting idea aside, the question still remains why does a dog give paw in the first place, what is the actions’ involuntary genesis?

In my view behavior is always in service to the movement of energy (rather than replication of genes) and so therefore there isn’t a mental link made between cause and effect in terms of a chronology of events or obtaining a material benefit. For example, a behavior can bring a sense of relief to an animal while at the same time causing it harm and yet the behavior persists and gets stronger because this far more fundamental mandate of relieving tension is being satisfied. So I see the body/mind as a "pipe" or conduit for for the transmission of energy (emotion) and the biggest or main pipe in the body/mind is the oral urge. In other words when an animal, the human animal included, feels powerfully attracted to something, an involuntary urge to ingest is autonomically aroused in order to satisfy a visceral hunger for connecting with said object of attraction. (As in "You’re so cute I could eat you up." or "I love that book, I could really sink my teeth into it.) A recent experiment demonstrated that when someone desires a new car or contemplates money, they actually salivate while looking at it.

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/09/110914154408.htm

However behavior is more complex than just trying to put attractive things in the mouth, and so there is another level of complexity wherein, if (a) the force of attraction is strong enough and yet (b) the object of attraction cannot be ingested, then emotion is deflected to a secondary "pipe," i.e. the forelimbs, and the extremities (paws/hands) become "energized," i.e. sensually aroused. Thus humans feel the urge to grab/fondle objects of attraction with our hands while dogs feel the urge to paw at things. The degree to which this contact is sensual satisfies the primordial oral urge at the root source of the impulse.

The distinction we need to understand however is that the hardwired reflex to paw, while genetically preprogrammed, becomes imbued with the sensual component from the physical memory of litter experiences when first born pups use their front paws to knead their mother’s mammary glands and which thereby induces a higher flow of milk. So the hardwired reflex plus the physical memory creates the emotional pipe of aroused paws since it has been indelibly imprinted with the feeling of flow. This imprint allows the adult dog to apply this behavior to a range of more complex situations so that when the dog finds itself emotionally moved, an object of resistance that through conditioning has become associated with that feeling of movement, such as an owner who has carefully house trained his puppy, can be made to move when the dog paws at him.

In my last post I referenced Dr. Wolpert’s thesis that every level of the brain, even advanced intellectual cognition, is predicated on solving the problem of motion. (The concept of Time would be the ultimate elaboration of this, i.e. how long it takes to move a certain distance.) The emotional circuitry I’m postulating is consistent with this organization. When an animal is attracted to something, it feels moved, literally, and its oral urge is engaged. The stronger the force of attraction the greater the urge to ingest and the faster the dog would run to connect with such an object of attraction. And then if the object moves, this gratifies the oral impulse. However when there is resistance to movement, this enables the second stage of the emotional circuitry so that the front paws are aroused to paw at it. We see another version of this when a young dog encounters a puddle for the first time. He’s attracted to it, especially if something is floating on the water, but is unsure at the same time, hence the perception of resistance between the oral urge and the dog’s capacity to fulfill it and he paws at the water, occasionally lapping some up in order to satisfy the oral urge which is always at the root of any given behavior.

In the final analysis the dog isn’t pawing at its owner with any of the above thoughts that were cited at the outset of this article. Rather the dog’s mind is organized so that an object of attraction is assessed in terms of motion and/or in terms of resistance to motion. If there is a perception of resistance then emotional arousal shifts from the jaws to the fore limbs as the basis of a response. The physical memory of flow becomes affiliated with the physical movement of the body in motion, the front paws kicking out with every stride that leads the dog toward an object of attraction, and inversely and in mirror fashion, when the dog perceives something moving this too becomes synonymous with that same feeling of flow. So in essence, the dog isn’t actually pawing at something in order to get it to move per se, even though its pawing may indeed have that effect, but rather the dog is in the tentative first stages of running-in-place because it already feels movement and is at the same time experiencing resistance. (Later I will explore this more deeply with the phenomenon of Pavlov’s drooling dogs). And in mirror fashion, an owner feels an urge to get up and move as well, albeit with the understanding that when it comes to letting a dog outside to take care of matters, he better make it snappy.

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.