When Training Isn’t Enough

Managing personality disorders in dogs

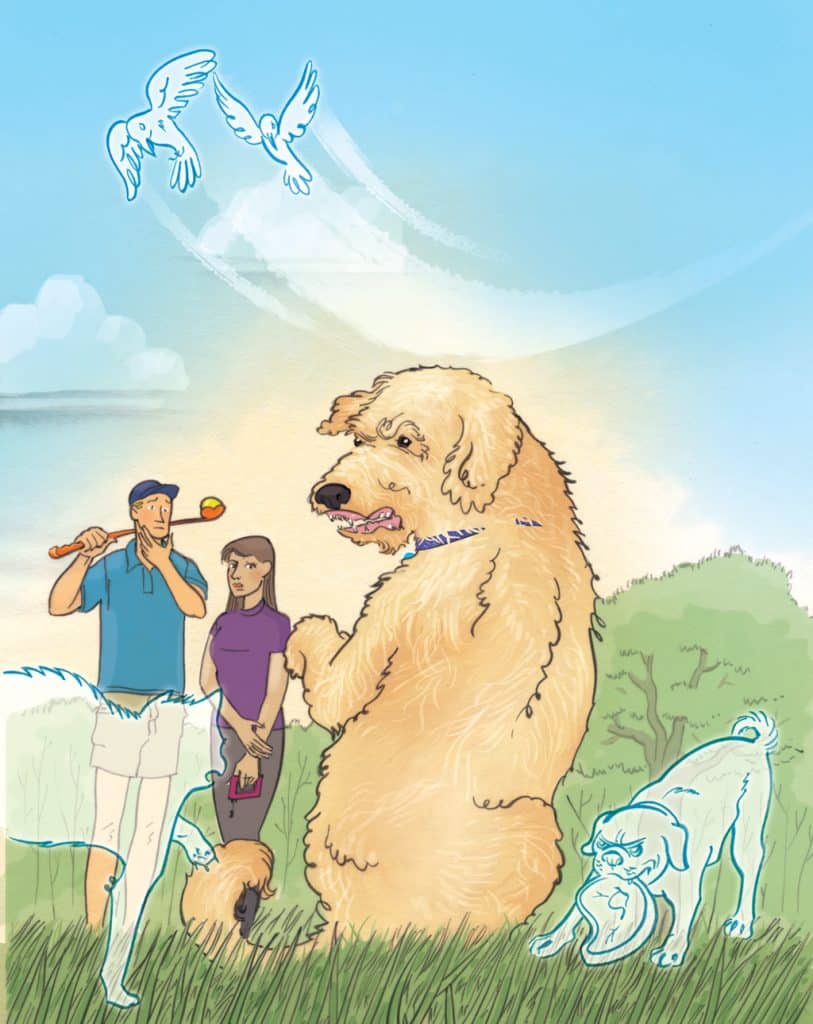

Briggs, Judy’s four-year-old Labradoodle, never had an easy time around strangers. He’d bitten several and couldn’t be trusted around most people. But unlike most aggressive dogs whose behaviour is fear-based and predictable, Briggs could be sweetness and light one moment, then a fire-breathing dragon the next. Though Judy had made some progress with the help of a local trainer, Briggs’ “Jekyll-and-Hyde” behaviour had everyone stumped.

It took an experienced pet behaviourist to recognize the root of Briggs’ problem. While watching the dog eat, he observed that Briggs would randomly stop, then dart his head about erratically, as if watching a fly buzz around. Except there was no fly.

Briggs was hallucinating. After a neurological evaluation, it was discovered he suffered from a form of epilepsy, causing him to hallucinate and become disoriented. This became the trigger and multiplier for his unpredictable aggression. He wasn’t fear-aggressive in the classic sense, but rather a delusional fear-biter.

Prescribed several medications, Briggs’ hallucinations gradually ebbed. But years of neurologically induced delusions had left psychological scars and conditioned Briggs to distrust. He’d require medication and behavioural management for the rest of his life.

Nature versus Nurture

Psychologists once believed that, though heredity did play a role in behaviour, anyone, given the optimal upraising and conditions, could become well adjusted and happy. Current studies have shown otherwise; those suffering from personality disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, attention deficit disorder (ADD), and even obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) show genetic predispositions toward these conditions and need medication to manage them. Though environmental factors can and do play an immense role in behaviour, it’s often genetics that defines the disease.

Though trends in psychology point more and more to genetics as a major cause of psychological disorders, populist trends among dog trainers and pet behaviourists still focus almost exclusively on “nurture” as the main cause of bad behaviour. “It’s not the dog, it’s the person” has become an anthem among animal advocates across the world. But this point of view ignores how organic, brain-specific defects and inbred psychological tendencies can profoundly affect a dog’s attitude, behaviour, and health, independently of anything her guardian does or doesn’t do.

Psychoses and Neuroses

The term psychosis defines a mental state in which the subject has a true break with reality, caused by a brain tumor or stroke, an inherited condition such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, an infection or a reaction to a drug. During a psychotic episode, a patient can suffer delusions, hallucinations, paranoia, or disorientation. Largely unresponsive to outside input, psychotics must be treated with drugs in order to gain control over the symptoms. Dogs who exhibit psychosis can be perfectly calm one moment, then enraged the next. Not completely aware of reality, these dogs usually can’t respond to commands or differentiate between a real or imagined threat. Though rare in dogs, it does happen.

Neurosis, on the other hand, involves a mental state in which the patient is under emotional duress, but still able to respond to stimuli. A neurotic dog knows what is happening, but cannot necessarily respond in a “normal” fashion. Neuroses can have genetic or environmental causes, or a combination of both. For instance, if a dog is extremely hyper-vigilant toward other dogs and her guardian punishes her for it (or puts her into a highly social environment too quickly), the neurotic behaviour will only get worse. Obsessivecompulsive dogs (stress-induced chewers, separation anxiety sufferers, or incessant pacers, for instance), though capable of being managed, are nevertheless driven to the behaviour through a combination of genetic and environmental conditions.

Dogs Get Depressed Too

Anyone who has seen a dog grieve over a deceased owner or dog friend knows that dogs can, like humans, become depressed. This can cause a variety of behavioural problems, including eating disorders, housetraining mishaps, escape, and even aggressive episodes, especially toward younger dogs. Generally, the depressed dog will eat and drink less, sleep more, be less responsive to commands or invitations to play and in general appear sad. She might develop a compulsive licking or chewing behaviour or even wander the home or neighborhood looking for the lost friend. The good news with dog depression is that it’s usually not genetically based and often resolves itself over time. In rare cases, though, medication may be temporarily necessary.

Hypo- or Hyperthyroid?

Aberrant behaviours in dogs can sometimes be the result of hormonal, not environmental factors. A common example is when, for a variety of medical reasons, a dog’s thyroid gland either overproduces (hyper) or under-produces (hypo) hormones which regulate metabolism. Hypothyroidism often results in lethargy, weight gain, hair and skin disorders, and other metabolic symptoms, while hyperthyroidism, a less common condition, causes weight loss, overeating, hyperventilating, and excessive thirst. Oddly, both conditions can result in a more irritable, less trustworthy pet. Behaviour modifications cannot cure these conditions; only diagnosis and treatment by a veterinarian can. It becomes essential then, to rely on your veterinarian and an experienced behaviourist to identify and treat the issue.

Signs of a Problem

Nothing is less fair to a dog than to discipline her for behaviours she is not capable of controlling. It becomes vital then to know the difference between a disobedient dog and one behaving badly due to a deep-seated neurosis or a genetically caused psychotic condition.

Symptoms of neuroses can include:

- Compulsive licking or chewing on herself or objects

- Constant panting or drooling

- Continuous pacing, whining or compulsive tail chasing

- Excessive barking

- Itching with no discernible cause

- Compulsive digging or fence running

- Habitual destructive behaviour

- Unpredictable changes in behaviour, mood or personality

- Incessant herding of people or pets

- Hiding, especially when strangers visit

- Profound antisocial behaviour, especially toward non-threatening pets or people

Unlike neurotic behaviour, which is often triggered or intensified by an outside stimulus (such as a stranger or a loud noise), psychotic behaviour needs no such trigger. It can appear or disappear on its own, without the dog even being aware of what’s happening.

Symptoms of psychoses include:

- Wildly unpredictable mood swings and/or behaviour

- Uncontrollable rage toward people, animals or inanimate objects

- Hallucinations

- Barking or growling at nothing

- Complete loss of appetite

- Bizarre responses to ordinary stimuli

- An inability to respond to human input

Thankfully, true psychosis in dogs is rare. Though it is often genetically based, psychotic behaviour can be brought on by diseases such as rabies or distemper, by drug or toxin overdose, or by trauma to the brain.

Dealing with Personality Disorders in Your Dog

Everyday personality quirks of dogs—excess barking, suspicion of strangers, pushy or fearful behaviour, housetraining issues—most of these can be dealt with without professional help by maintaining a regular obedience/training regimen, providing your dog with structure, routine, and plenty of enrichment activities (games, trick training, walks, chew toys, etc.), and by socializing her in a reasonable, measured fashion, with people and other pets who are well adjusted and tolerant. But if threatening, unpredictable behaviours of the types listed earlier suddenly begin it becomes vital for you to seek out professional help.

Your first stop should be your veterinarian who will determine if injury, hypothyroidism, epilepsy, cancer, or some other organic malady is causing the change in behaviour. Often, medication (as with Briggs) can reduce or eliminate a serious issue.

“There are a vast number of behaviour disorders in dogs that respond to behaviour-modifying drugs,” says Dr. Susan Mailheau, a Seattle, Washington-based veterinarian. “These include Clomipramine, Fluoxetine, Benzodiazepine, and Phenobarbital.”

Clearly, the right prescription could mean the difference between an uncontrollable, despondent dog and one who can again be controlled, trained, and trusted.

Care, though, must be taken when discerning between simple disobedience or quirks and a true personality disorder. Guardians of dogs acting out inappropriately solely because of spoiling or lax training can often be convinced to try mood altering drugs to “cure” the problem when all that is really needed is a change in how the dog is treated, trained, and managed. Anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, and other mood-altering drugs should be considered only after the condition is shown to be deep-seated and unresponsive to behaviour modification. “A drug can cause an undesired effect if used on the wrong dog,” adds Mailheau. “For example, a shy fear-biter given an anti-anxiety drug could become a more overtly aggressive dog due to the drug’s capacity to inhibit her shy nature.” In other words, if your dog is simply behaving badly, it’s inappropriate and perhaps irresponsible to try to medicate the misbehaviour away.

Behavioural Evaluation

Even if your dog does have serious neurotic or psychotic issues, an experienced behaviourist should help you plan what to do after medication has begun. The behaviourist can determine if a misbehaviour is simply learned (and therefore treatable with behaviour modification) or truly engrained in your dog’s psyche. And, even if a medication removes the biochemical cause for the misbehaviour, the behaviourist will be able to help your dog get over the conditioned responses she’s developed over time in response to the medical condition.

Briggs takes his medication and continues to work with trainers in hopes of extinguishing the conditioned responses he developed to cope with years of undiagnosed brain dysfunction. It is still a day-to-day struggle for Judy, but her love for her dog remains the best remedy for a condition that might cause others to consider euthanization. With the caring attention of a quality veterinarian, and the help of a good behaviourist, dogs like Briggs can be managed and given another chance.

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.