A New Breed of Therapy

Sometimes the best therapy is simply the company of a dog

Lisa Peacock has always loved animals, which is fortunate, as they’ve helped her through some very tough times. As a young girl growing up in Arizona, she begged her dad for a pet, so he got her a rabbit and then surprised the whole family with a loveable puppy named Bruiser at Christmas. Tragically, it was the last Christmas they spent together—Lisa’s father was killed in the Northwest Airlines Flight 255 plane crash on August 16, 1987. Lisa was just nine years old.

“My life,” she said, “was turned upside down.”

The family attempted to cope by adopting more animals, including horses, a cat, and a goat. But Lisa’s mother also married someone Lisa describes as a verbally abusive alcoholic.

“I went from the trauma of losing my dad to the reality that the new dad I had was not nice and caused a lot of pain and hardship,” Lisa said. “Whenever things would happen or I wanted to avoid him, I went to the animals.”

By the time Lisa was a senior in high school, things were looking up; her mother left her stepfather and the family was mending. But a year later, when Lisa was a 19-year-old college freshman, Lisa lost her mother, too, in a car crash.

“My entire world just collapsed again,” she said.

But Lisa’s mom had given her a final gift: before her death, she had made her family reservations for an overnight at the Phoenix Zoo. Despite their recent loss, Lisa and her sisters—an older sister and a 6-year-old “baby” sister—decided to go anyway. Lisa said at the zoo, she “felt good for the first time in a long time.” An employee noticed Lisa’s connection with the animals and suggested Lisa apply for a job at the zoo. She did so the very

next day.

Lisa worked at the zoo for the next three years while she finished college and credits her access to animals with helping her heal and avoid pitfalls like drugs.

“What animals need is food and shelter and love and excitement, and I could give that. It was so nice to have something in my life that was not affected by what I had been through and didn’t care if I kept crying.”

In fact, Lisa had keys to the zoo and could visit a collection of about 100 animals whenever she liked.

“I was able to go into the enclosure with the wallaby and rabbits and just feed them and sit with them, and go into the enclosure of the owl and pick her up and take her for a walk … They loved it because it gave them enrichment, and I loved it because I got to be around something that wasn’t going to pity me. To them, I was okay.”

After graduation, Lisa moved to Los Angeles—“There was such possibility in going somewhere else where I didn’t have any memories” —and worked at a zoo before knee surgeries sidelined her. A co-worker asked what she really wanted to do with her life. To her surprise, she immediately answered, “I want to start a program where I can work with animals and grieving children.”

With that, the idea for the Peacock Foundation was born. Lisa got a master’s degree in marriage and family therapy and called on animal-loving friends to help launch her nonprofit. Initially, she would travel to schools with exotic animals such as her Burmese python and chinchilla to counsel children, but after she adopted a dog named Ricky who had been rescued from an abusive home, the Peacock Foundation found its model.

Lisa and Ricky, a retriever mix, began visiting kids at foster facilities and the response was incredible.

“I would tell them all his story—how the first family that had him didn’t treat him very well. And we would talk about how I helped him through that, and what things he still carried because of that time of his life and what it was like to be adopted,” she said. “So it gave this huge platform to be able to talk to kids about all these different issues that might be going on in their lives—and a chance to see there is recovery.”

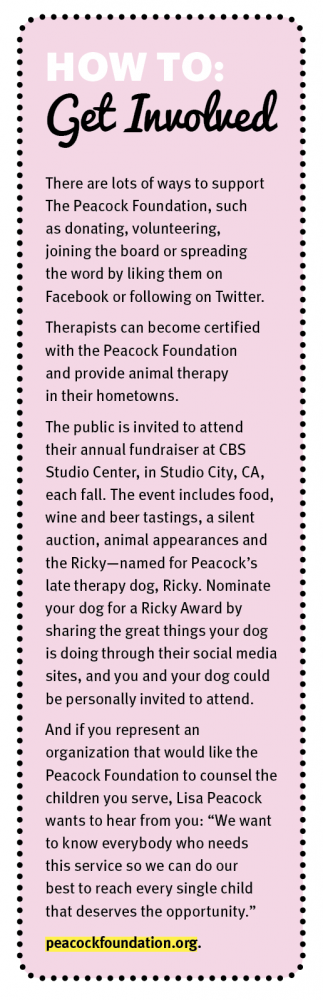

Now the Peacock Foundation has expanded to include volunteer therapists and animal handlers—primarily dog owners—who visit at-risk children in schools and homeless shelters for group therapy. The Peacock Foundation offers two eight-week therapy sessions—for free—to schools and mental health agencies and has counseled over 5,000 children in Southern California. To expand that reach, the Peacock Foundation has also started offering training for therapists who want to learn how to incorporate animals into their practice.

“The point is to help these kids develop their self-worth and resiliency and coping skills,” Lisa said. “This all started because I had a hole somewhere in me and this filled it … And I want to make sure other people who are going through that, instead of sinking down into a depression or feeling lost and hopeless, they find something that can make them feel purposeful and connected.”

She said she’s seen children with anger issues, violent tendencies, and depression open up to her simply because they were petting a dog together. One of her first cases involved a three-year-old boy who had been placed in a foster home. He would cling to Ricky’s fur while standing next to him. A month later he was transitioned to a new home and reunited with his brother, and when Lisa arrived with Ricky, the youngster ran to Ricky, excited to show off his canine friend to the new family.

“We saw these two little boys who had been through so much in such a short amount of time be able to bond and transition so much better because of their access to animals. I saw the way this little boy lit up when Ricky would walk around the corner. It gave me a language with him that I wouldn’t have had,” she said. “That has happened so many times.”

“I’m not just another therapist who’s going to talk to them about bullying or alcohol and drugs—I actually brought something for them,” Lisa said. “What I’ve noticed in working with all these various kids is because I offer something, they offer something back.”

Pamela Sprankling, MFT, a licensed marriage and family therapist, attended a Peacock Foundation training to learn how to integrate animal therapy into her practice in 2013, and was so impressed with its effectiveness that she now volunteers for the nonprofit and joined the board of directors last year.

“When kids walk in and there’s an animal, they just change,” Sprankling said. “They just light up—it’s like a magic wand.”

In one particularly moving instance, Sprankling led a therapy group that included a depressed 14-year-old girl. When the group started, the girl made no eye contact, rarely spoke, and was hesitant around the dog. But when a rescued terrier mix named Buddy was visiting, she suddenly shared that a friend of hers had been killed in gang violence.

“I turned to the handler and said, ‘Has Buddy had any losses in his life?’ The handler talked about other dogs he’d had that had died, and how Buddy was sad because dogs get depressed,” Sprankling recalled. “Then it takes it off the kids because the animal has had loss too.”

After Buddy’s handler shared that Buddy didn’t eat for a while, had sleep issues, and got cranky, Sprankling was able to say, “Buddy has had losses too, and he made it and looks happy today.” By the end of the eight-week session, the formerly withdrawn girl had blossomed into a group leader, even volunteering to help the other kids.

“When you bring in an animal, the focus goes to the animal. I think that’s the key: the safeness. It’s nonthreatening, and it’s fun! They don’t even know they’re having therapy,” she said. “The animal will open the door to something that a therapist alone can’t do.”

Marwick Kane, an animal handler volunteer with the Peacock Foundation, visits group therapy sessions with his Doberman Pinscher, Jackie, or his long-haired Dalmatian, Kai. He’s seen shy children learn to speak up by talking to the dogs, and aggressive children learn to be gentle. If kids get too rowdy or stop listening to the counselors, he explains he has to take his dog outside until they calm down—so the kids will be good to keep the dog in the room.

Though the children he works with are of diverse economic backgrounds, their reaction to the dogs is universal. “All the kids are having the same issues,” Marwick noted. “There’s no difference whether they come from millionaire parents with guest homes and swimming pools, or they’re living in a homeless shelter. Their reaction to the dogs and how it helps in their temperaments—I have not seen a difference. It’s amazing.”

Though some volunteer animal handlers bring in turtles or birds, he said dogs are the “biggest hit.”

“I think people wonder why there’s such a connection with the therapy dogs. For me, all I can say is there’s no barrier between the dogs’ soul and their eyes. Humans put up barriers constantly—you always wonder what someone’s thinking, what they’re feeling. Dogs don’t do that. You look at a dog, and you’re happy.”

Kane said he thinks people should seek volunteer experiences involving something they love—which in his case is animals, just as it is for other Peacock Foundation volunteers and of course, the group’s founder.

“Lisa Peacock is a very compassionate person, and she’s an animal person. Clearly this is a passion for her. This is not just a job or a business—this is passion. And when something comes from passion, it shows,” he said. “She is fantastic.”

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.