Do Dogs Grieve Over A Lost Loved One?

Emotions, loyalty and grief

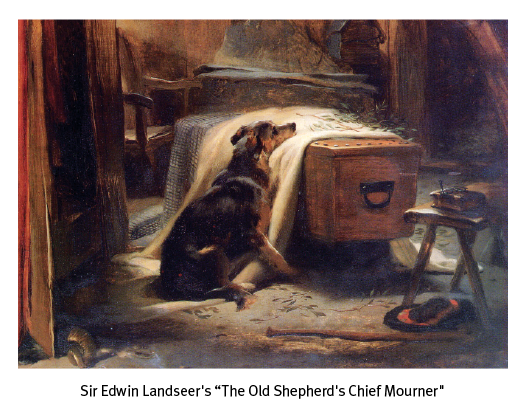

I recently attended a lecture given by an eminent art historian about how the emotions of animals and humans have been depicted in artworks over the centuries. At one point in his talk he showed a photo of Sir Edwin Landseer's 1837 painting, “The Old Shepherd's Chief Mourner.” The central figure in this painting is a dog who rests his head on the simple wooden coffin of his human companion, the old shepherd of the painting's title. This scholar's comment was that this was one of the most perfect representations of grief in a dog. He went on to say, “The fact that this dog refuses to leave this man's side, even after his death, highlights the close relationship that the dog and the man had. It also demonstrates the depth of the grief that the dog is feeling.”

I have always been very fond of this painting, moved by the emotional bond they clearly shared and by the loyalty the dog has for his master. There is no doubt that a dog in this situation would feel sorrow, perhaps depression, and a deep sense of loss. But behavioural scientists often debate whether dogs actually feel grief when a loved one dies. Those that doubt it suggest that grief requires some concept of the nature and implications of death. This is beyond the mental ability of human children before the age of four or five years, and since evidence suggests that dogs are mentally and emotionally equivalent to humans aged two to three years of age, this would place the concept of death beyond both dogs and young children.

To get an idea as to what may be going on in a dog's head when a loved one dies we can look at what goes on in the mind of a child in the two to five year age range. These children do not understand that death is irreversible. It is common for a young child to be told something like “Aunt Ida has died and won't be coming back,” only to have the child ask a few hours later “When will we get to see Aunt Ida again?” Children do not comprehend that the life functions of their loved one have been terminated and this is reflected in their questions as they try to understand the situation. They ask things like: “Do you think we should put a sandwich or an apple in Grandma's coffin in case she gets hungry?” “What if Daddy can't breathe under all that earth?” “Will Uncle Steve be hurt if they burn him?” “Won't Cousin Ellie be lonely in the ground by herself?” In the absence of an understanding of death there can be pain and sorrow and depression, but the behavioral scientists suggest that this is different from the more adult feelings of grief which includes a recognition that the death of a treasured companion involves a loss that is permanent.

In my own home, I saw the heartache and sorrow that the loss of a loved one could bring to a dog when my cherished Flat-Coated Retriever, Odin, died. My Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever, Dancer, had lived with Odin every day since Dancer was eight weeks of age. They would play together for hours and simply seemed to enjoy each other's company. With Odin now gone, Dancer systematically looked at each of the four locations where his friend would go to lie down. After doing this several times he wandered to center the of the room, looking around forlornly and whimpering. His anguish only gradually wound down and it was several weeks before he stopped checking all of the places that Odin should have been whenever he came home from a walk. Much like one might expect from a child who did not understand the concept of the permanence of death, Dancer never gave up on the idea that Odin might reappear. Up through the last year of his long life Dancer would still rush toward any long-haired black dog that he saw, with his tail batting and giving hopeful barks as if he expected that perhaps his friend had returned.

This is what I think about when I see things like the photograph of Jon Tumilson's funeral. After the Navy SEAL was killed in Afghanistan in 2011, more than 1000 friends, family, and community members attended his funeral in Rockford, Iowa. The mourners included his “soul mate” Hawkeye, a black Labrador Retriever. With a heavy sigh Hawkeye lay down in front Tumilson's flag-draped casket. There, the loyal dog stayed for the entire service. Was he grieving? No doubt he was feeling depressed, sad, and lonely, but also he might well have been waiting, hoping, that his master would return. Perhaps he might get out of the coffin and return to a life with his now lonely dog. This might well be the motivation behind the dogs who have waited for many years at the graves or other familiar sites associated with lost loved ones, such as Greyfriars Bobby, the Skye Terrier of 19th-century Edinburgh who is famous for supposedly spending 14 years guarding the grave of his owner until he died himself on January, 14, 1872. There is sorrow associated with this waiting, but perhaps something more positive than grief. Because dogs do not have the knowledge that death is forever, at least there is the option to hope—a hope that a loved one might come back again.

Dogs, in their ignorance of the true meaning of death, when driven by their unhappiness and motivated by their hope, may sometimes engage in desperate or irrational acts to deal with the sorrow caused by their separation from someone dear to them. Consider the case of Mickey and Percy. As in the case of Dancer and Odin we are again dealing with a dog who lost a housemate and a friend. Mickey was a Labrador Retriever owned by William Harrison and Percy was a Chihuahua given to Harrison’s daughter, Christine, when Mickey was already a young adult. Despite their size and age differences, the two dogs were good friends and playmates until one evening in 1983 when Percy ran out into the street and was hit by a car. While Christine stood by weeping, her father placed the dead Chihuahua in a crumpled sack and buried him in a shallow grave in the garden.

The depression that fell on the family seemed to affect not only the humans, but also Mickey, who sat despondently staring at the grave while everyone else went to bed. A couple of hours later William was awakened by frantic whining and scuffling outside the house. When he investigated the noise, he saw to his horror that the sack in which he had buried Percy was now laying empty beside the opened grave. Next to it, he saw Mickey, who was in a state of great agitation, standing over Percy's body, frantically licking his friend’s face, nuzzling and poking at the limp form in what looked like a canine attempt to give the dead dog artificial respiration.

Tears filled the man's eyes as he watched this futile expression of hope and love. He sadly walked over to move Mickey away when he saw what looked like a spasm or twitch. Then, Percy weakly lifted his head and whimpered. It would be nice to believe that it was some deep sense in Mickey that had recognized there was a faint spark of life in the little dog, however it is more likely that it was his lack of understanding of death that was behind his actions. Rather than being swamped by grief over the permanence of dying, Mickey was left with hope for the return of his well-loved little housemate. Hope seems to have motivated him to make one last try to save his tiny friend—and this time it worked! Percy made a full recovery thanks to his faithful friend and they spent further happy years together. Perhaps incomprehension of the permanence of death is something we should envy in our four-legged friends.

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.