Dead Dog Love Story

Finding love through pets lost

When Richie and I met—a bitterly cold night in January 2012 at a South Boston dive bar—three things dominated our first conversation: our terrible nasal problems (Richie also has horrendous allergies, and I was getting over a sinus infection when we met), our love of large American-made cars (at the time Richie drove a 1986 Chevrolet El Camino, and my first car had been my grandparents’ 1993 Cadillac Sedan DeVille), and our dead dogs. Richie and his family had just put down their family dog, Cocoa, a month before we met in December 2011. Though by January 2012 my childhood dog Gus’s death was more than five years behind me, listening to Richie talk about how hard it had been to watch Cocoa collapse, how the vet hadn’t warned his family how quickly it would happen, I felt all the old feelings come up again. It was hard to listen to, but at the same time, it felt good to talk about. Richie missed Cocoa; I missed Gus. This guy didn’t think it was weird at all to get choked up talking about our dead dogs over bottles of Narragansett in a loud bar.

Soon after Richie and I met, I moved to New York for an MFA program while he stayed in Boston. While we were not officially dating during this time, we kept in touch, and I told him updates I got from my parents about how my other childhood dog, Gwen, was starting to decline. By July 2013, a year-and-a-half after we’d met, I was living with my parents at their summer house between semesters of grad school, and it was Gwen’s time. She was euthanized at a small veterinary practice in Connecticut, and we brought her body back to my parents’ house, where we buried her in the yard under a brilliant blue hydrangea bush.

When I texted Richie that Gwen was gone, he knew how to be there for me. He called me that afternoon after we had buried Gwen, and we talked for the better part of an hour. Richie gave me space to remember Gwen—how we would know a thunderstorm was coming when she would hide behind the bathroom door, how in her “cocktail years” she would only eat chicken lovingly prepared by my mom and not store-bought dog food, how she would flush pheasants from the tall grass, how she always got carsick, the one time she killed a snake, how Gwen would snuggle into the corner of the sofa next to you. Talking to Richie, I was able to remember all the things about Gwen that made me laugh and brought me joy, which helped remind me why having a dog is worth it, despite the terrible grief I was feeling at that moment. In fact, I was only feeling such terrible grief because it had all been so good—and I realized that I wouldn’t trade the good parts for a minute just to avoid how I was feeling now.

“It’s like choosing never to date or love someone because you might break up one day,” Richie said. Better to have loved and lost, I thought, than never to have loved at all.

Richie continued to check in, texting me to see how I was doing, and he sent me a sympathy card and David Bowie’s album Low on vinyl to make me feel better because I was feeling “low.” He got it. It still sucked that Gwen was gone, but it felt good to know someone understood.

After finishing my program in New York, I moved back to Massachusetts and into an apartment in Cambridge, where Richie eventually moved in with me. He brought his bass and guitar, his fish tanks and bonsai trees, and, of course, he brought his dead dog’s leash with him, too.

“This was Cocoa’s,” he told me, showing me the worn green leash as he unpacked. “We have to hang it by the door.” I didn’t question it—people do what they need to do to remember their pets. Richie explained: “That way, in case there is a fire, I can grab it on my way out.” I nodded; this made perfect sense to me. We put a nail in the wall, and the leash hung down by the door as if Cocoa’s ghost was ready to be taken for a walk at any moment. The strip of green looked lonely on the white wall all by itself. We studied it together, and then I said, “Wait, I have something to add.”

I went to the bedroom and over to my jewelry box where mixed in with my rings and pins and beads and buttons, were two collars—a thick, worn blue one that had belonged to Gus, and a thinner, cleaner pink one patterned with white paw prints that had belonged to Gwen. I hooked the two collars up on the nail with the leash. “Now, if there is a fire, they’re all together.”

Richie nodded. He understood, and, not only that, I felt that he respected my grief and honored my love for my past pets, and let it have space in our home. Pets are family members, and Richie knows that you don’t tell someone to “get over” their grief when a family member dies. Richie knows that even long after a pet is gone, talking about that pet, sharing your favourite memories are a way to keep your loved one alive. Not only does Richie understand all this, but our families do too. Growing up, my dad told me stories about his old dogs—Prince and Brand— and I thought of them as my family elders in the same way I thought about my great-grandparents or long-lost cousins. When I first went over to Richie’s parents’ house, I noticed right away the framed photo of Cocoa next to the box of her ashes and a small stuffed brown dog on the bookshelf.

In 2018, I had already known—for all these reasons and many others—that Richie was the person I wanted to spend the rest of my life with, but the moment that really sealed the deal was when my parents told me they were going to sell their summer house. I understood their reasoning: too much house, too much work, too many expenses, they were getting too old. But I wasn’t listening to their reasoning—all I could think about was Gwen. If my parents sold the house, what would happen to the skeleton of a fourteen-year-old Cairn Terrier buried under a hydrangea bush in the backyard?

Even death is impermanent, it seems. There is no final resting place. The house that my parents were selling—I knew they wouldn’t have it forever. With me and my siblings grown up, they didn’t need all that space. I knew it was coming. And, yet, I didn’t think about that when we buried Gwen in the backyard. In our grief, at that moment, it just seemed like the right thing to do. Gwen loved that house. She sat under a hydrangea bush in the summer when it got too hot, enjoying the blue flowers’ cool shade. This is where she would want to be for eternity, I had thought then. But now, knowing the house was to be sold, I began to breathe shallow, fast, breaths. Would Gwen forgive us for selling her grave out from under her?

"In fact, I was only feeling such terrible grief because it had all been so good."

I began to cry when I got off the phone with my parents, and before I could even say anything, Richie gave me a hug and said, “If you and your parents want, I’ll dig her up.” I started crying harder—now not just from the grief of losing Gwen’s final resting place, but from an overwhelming sense of gratitude for how generous and understanding Richie was in that moment. No one, it had seemed, understood dead pets more than Richie, and here he was now offering to exhume the body of my five-years-dead dog if it was what my parents and I wanted.

I felt so alone in those moments watching Gus and Gwen sink down onto the vet’s stainless-steel table, pink tongues flopping out at unnatural angles—but I wasn’t. I never was. My parents were in the room with me—they got it. The vet was there, too—she got it. So did the vet techs and the animal hospital receptionists—they got it. The people who commented on my Facebook memorial posts, who mailed sympathy cards, who texted to see how I was doing—they got it. Richie, his family, my friends—they all got it. When you love animals, you have to find your people. It may seem counterintuitive, but that’s what it’s all about. When an animal you love dies, the thing you need the most to help you get through it is a community of fellow human beings. When Richie and I finally got married in the summer 2021, I knew that we would have each other in sickness and in health, in the hard times and the good, and we would be there for each other every time an animal we loved died.

In the end, my parents sold the house and we left Gwen buried in her spot under the hydrangea bush. That house had been the place she loved the best, and it felt right for her to stay there. On the last weekend we spent there before the new owners took over, Richie and I walked around the house, visiting her grave. I squeezed his hand, knowing what he had been willing to do for me, because he gets it. And I smiled as I pictured a little dog ghost haunting the backyard.

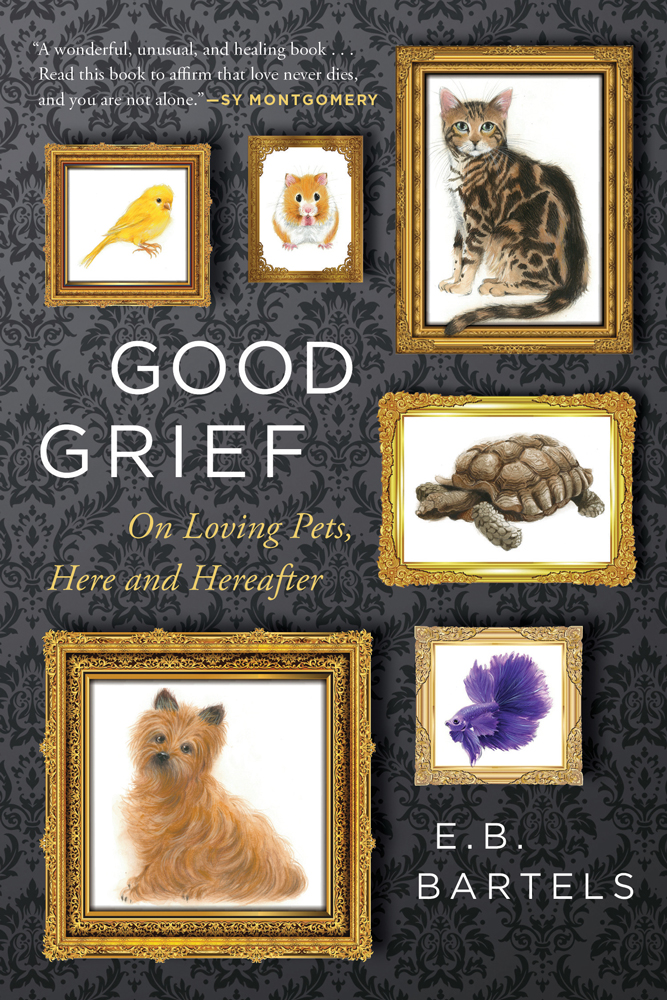

E.B. Bartels is the author of Good Grief: On Loving Pets, Here and Hereafter available now from Mariner Books/HarperCollins.

This article originally appeared in the award-winning Modern Dog magazine. Subscribe today!

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.