The Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever

A true Canadian canine (eh?)

Most people are quite curious the first time they see my Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever. “What breed of dog is that?” they’ll ask, as my hairy rusty-brown and white canine companion furiously wags his tail, ever hopeful of getting a treat.

“Is it a miniature Golden Retriever? A Border Collie cross? A Brittany Spaniel?”

I respond by saying the name slowly-“It’s a Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever.” I annunciate my words carefully, for more often than not, the person will reply, “Um… That’s interesting… A Troller, you say?”

“No,” I laugh, “Trolling is a way of fishing and most dogs can’t hold fishing rods! This is a Toller.” And then I begin to relate their story.

While many people think this is a new breed, the origins of the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever (NSDTR, or “Toller”) run deeper than many of today’s better known and more established breeds. One of only four truly Canadian breeds-the other three being the Labrador Retriever, the Newfoundland and the Canadian Eskimo or “Inuit” dog-its roots can be traced back to a time when the Canadian Maritime provinces and parts of the state of Maine were still known as Acadia. The earliest documented reference to the type and its use dates back to about 1630. By the early 1900s, the area around Little River in Yarmouth County, Nova Scotia, was being credited with having produced a unique type medium-sized, rusty-brown dog that bred “true” (i.e., offspring reliably resembled their parents)-hence the dog’s first unofficial name, “Little River Duck Dog.”

Anna-av/Bigstock

It is believed that the NSDTR was developed through crosses between the Chesapeake Bay Retriever and the Brittany Spaniel (the American Kennel Club’s “Brittany”)-with, perhaps, a little farmyard collie thrown in for good measure. Folklore maintains that the Toller resulted from a fox-dog mating, but as romantic as that theory sounds, science tells us it is genetically impossible. However there is a slight possibility of some coyote genes having entered the mix early on. (Coyotes are more closely related to domestic dogs than foxes are and can, in fact, interbreed with them.) Only God and Mother Nature know for sure!

In 1945 the breed was officially recognized by the Canadian Kennel Club, but up until the mid-1960s, it remained one of Nova Scotia’s best-kept secrets. Since then, however, Tollers have become increasingly popular across Canada and the United States, as well as in England, Belgium and Australia. In 1995 the breed was officially declared the Provincial Dog of Nova Scotia-the first and only breed to be awarded this distinction. And in 2003, on July 1 (Canada Day), the breed was fully recognized by the American Kennel Club-a fitting salute to a true Canadian dog.

Tollers have become popular partly due to their size (which is small, compared to any of the other retriever breeds), combined with their beauty, intelligence, versatility, strong working drive and friendly nature. But size and visual appeal should not be the determining factor in selecting a Toller (or any other breed of dog, for that matter) as a canine companion. A responsible breeder will warn you that this is not the best choice of dog for sedentary people! The Toller is a high-energy, high-maintenance breed that needs lots of mental stimulation and exercise. And for people who don’t like dog hair, be forewarned: these dogs shed. In fact, they shed a great deal. To minimize “snowdrifts” around the house, regular brushing is a must.

Life on White/Bigstock

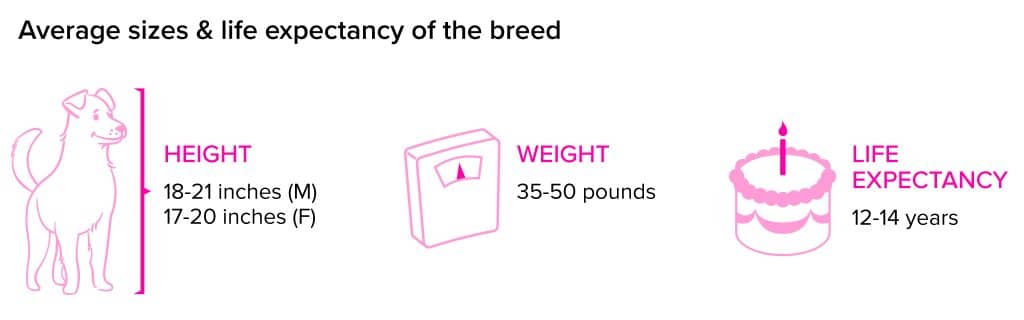

An adult male Toller weighs about 20 to 23 kg (40 pounds) and stands about 48 to 51 cm (20 inches) at the shoulder-about the same size as a large Brittany Spaniel. The coat is a rusty brown and the dog may have white markings on the feet, chest, face or tip of the tail. A complete absence of white is also acceptable. The nose, lips and eye rims may be all black (like a Golden Retriever) or all flesh-coloured (like a Brittany) but should never be a combination of the two colours. The Toller’s water-repellent double coat looks very similar to that of a Golden Retriever, which is probably why many people think these are unusually coloured “mini” Goldens.

Despite its boundless energy and strong desire to work, the Toller should not be stereotyped as “just” a hunting dog. This breed excels in all obedience and high-energy dog sports, including field trials, agility and flyball. Tollers are now also occasionally being used as service, drug-detection and search-and-rescue dogs. Much like Border Collies, they can be equally happy in rural or urban settings provided their needs for work (and play) and for sufficient exercise are met. Toller fanciers, who tend to be as fun-loving as their dogs, have been heard to describe these dogs as “clowns in red dog suits” or “Border Collies with an on/off switch.”

To understand what’s most special about the Toller, one must first understand a little about the world of hunting dogs. A pointer, for example, detects and then “points” at birds hiding in thick brush. With outstretched nose and raised front paw, a setter similarly “sets” game. Well, Duck Tollers “toll.” In her book A Breed Apart Gail MacMillan writes, “Tolling, in a hunting context, describes the process of luring game (usually waterfowl) with the use of small animals (usually dogs). This definition comes from one meaning of the verb ‘toll,’ which is to attract, entice.”

Jaromir-Chalabala/Shutterstock

Legend has it that early Acadian settlers developed the NSDTR’s unique hunting style through trying to mimic a hunting technique used by red foxes. (And this is, perhaps, where the fox-dog legend comes from.) A waterfowl hunter sets up in a blind near the edge of a lake or river. While sitting concealed, he (or she) will throw a toy or a stick toward the water’s edge. The tireless Toller eagerly retrieves the object… over and over and over again.

Foxes don’t throw toys-but one of a pair will hide in the bush while the other capers at the water’s edge, luring and distracting swimming ducks, drawing them ever closer, until fox number one can pounce. As the happy-go-lucky Toller cavorts near the blind, ducks rafted on the water are similarly attracted to the dog’s seemingly crazy antics and its waving, plume-like tail. Like a Border Collie, whose breeding and training tell him not to attack the sheep he herds, a well-trained Toller knows to ignore the birds on the water and to focus on the task of playing and retrieving. The tolling dog romps and prances along the shoreline, leaping and twisting, tail waving gaily. Occasionally it will splash in the water or disappear into the blind. Then it will suddenly re-appear and begin the “dance” all over again. Intrigued (or perhaps transfixed), the waterfowl swim closer to the shore. When they are within rifle range, the hunter calls the dog into the blind. After the shooting is over, the dog gleefully leaps into the water to retrieve any downed birds.

The unique, water’s-edge “dance” of the Toller has earned the breed the nickname “Pied Piper of the marsh.” The behaviour is so unique that in the 1960s, the amazing little Duck Toller was even featured in the Ripley’s famous “Believe It Or Not” newspaper column syndicated throughout Canada and the United States.

Gail MacMillan reflects in her book on the maladaptive, seemingly inane behaviour of the ducks: “Is it mere curiosity that draws ducks (and sometimes geese) to their doom? Or is it some strange phenomenon of nature, which will never be understood until someone deciphers the deductions of a duck? Whatever the explanation, the attraction has proven effective for hundreds of years.”

Field trial champion or much-loved family pet, the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever has come a long way from its beginnings as a hunting aide to the hardy and versatile canine companion we see today.

» Read Your Breed For more breed profiles, go to moderndogmagazine.com/breeds

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.