Ghost Dogs

In my book, Last Dog On The Hill, I discuss how growing up in a NY apartment afforded me no chance to own a dog, and how the only pet we did own back then was a parakeet named Chipper, a bitter bird who, blessed with super-avian powers, would bend apart the bars of his jail cage and escape to strafe and soil our heads while screaming primordial discontents. He wasn’t much fun.

Like every other red-blooded kid, I’d wanted a dog. More than other kids, maybe. But back then, I had to settle for Lassie, Old Yeller, Rin Tin Tin—you know, media stand-ins for tenement-bound wannabes.

That doesn’t mean I never got to experience flesh-and-blood dogs in my early days. I did. I lived vicariously through the dogs of friends, merchants, neighbours—dogs who today I call my “ghost dogs.” Only memories now, but so important. They got my “dog on” for me.

Jumbo

Jumbo was a Great Dane/Boxer mix owned by my grandmother in her apartment on Webster Avenue in the Bronx, in the early Sixties. How she got to have that behemoth in her tiny third floor walk-up, I’ll never know. A short, old-school Italian widow who’d raised eight kids, (including three WWII vets, one a decorated hero with Patton’s Third Army, and another killed in the Pacific theatre by, of all things, a tiger in the jungles of Bangladesh), my grandma was an immutable force, an example of one who endures at all costs. And so she got Jumbo, to amuse her, and to protect against those who might take advantage of an old yet still wily woman.

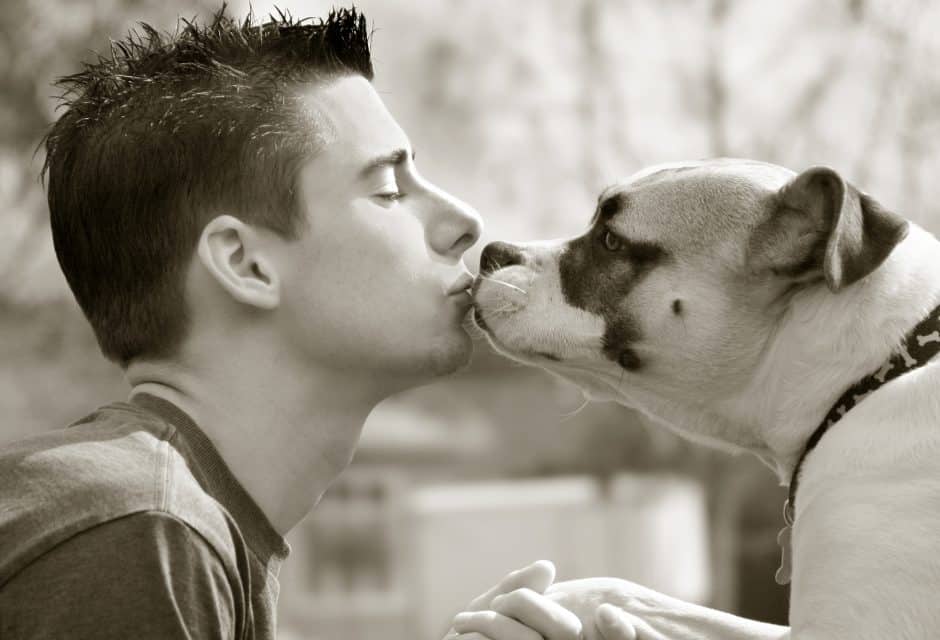

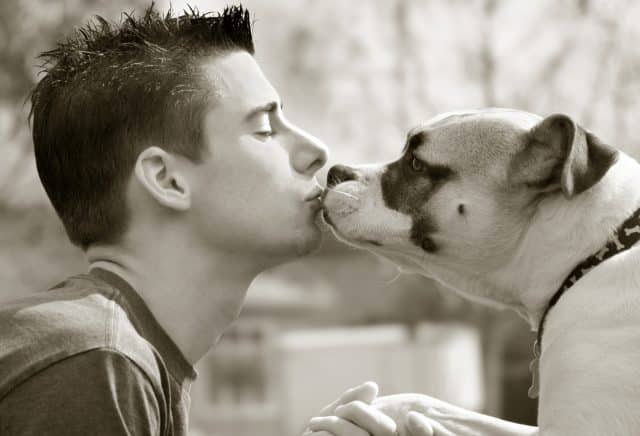

Fawn-coloured Jumbo had a lean Boxer head screwed onto a thick, Danish body. At about ninety pounds, he was no Harlequin, but had density of bone, and a ripped physique to be proud of. And, he outright loved me.

He also had little if any training, so when he’d see me once each week, he’d gallop over and pin my 38 pound, six year-old body beneath the Formica table in the kitchen- just bowl me over, plant his massive front paws onto my shoulders and slobber me up until I’d cry hysterically with joy, fear, awe- I’m still not sure. It was enjoyable, I suppose, in the same way that being tickled into incontinence is enjoyable.

My dad would eventually step in and drag the brute off of me, lock him up in the bedroom, and wipe my face off with a dish rag while Jumbo would head butt the old wooden door, whining out his affections like a four-pound teacup Poodle. And so, I remember Jumbo, whose Herculean body finally gave out on him there on Webster Avenue.

Dino

Ah Dino, the sweetest gas station sentinel I ever knew. Late Sixties, my dad worked a weekend job across the street at the Sinclair gas station, owned by his friend Louie Argenta, a red-haired, freckle-faced Italian and ex paratrooper who’d taken shrapnel during the war, and would every few years cough up a piece of it, just spit it right out and laugh as the jagged, bloody shard skipped across his desk, mechanics and friends staring silently as lung blood dripped from Louie’s grinning lips.

Dino was the gas station’s mascot and protector, a thick-bodied, low-riding German Shepherd, coal black with strokes of rust on his chest, face and legs. He lived and died there at the station.

Dino looked like what a German Shepherd might have looked like 5000 years ago, if the breed had existed then, like a hulking dire wolf with a coarse coat greased up from years of gas station living, as if Louie brushed Brylcreem into it every morning. With fangs long as crayons, and an old-school, squared-off conformation, Dino came off like a Russian power lifter, a sweetheart who could tear a burglar’s throat out then smile at whoever opened up at six in the morning.

My mom would send me across the street to the station to call my dad up for dinner. I’d walk over quietly for a chance to eavesdrop, to hear men talking frankly, to catch my dad spouting off like one of the guys. Then I’d skip into the motor oil-scented office to announce dinner.

Often, I would I’d cross over early and pass through the side gate where Dino lived, the powerhouse who could have killed me with a snap of his jaws. I had no fear of him at all, I just thought he was my friend.

I’d bring him something—a swipe of meatball, a tear of provolone—anything to make him happy. He’d see me coming and that thick, black, barely feathered tail would start rowing the air, and when I walked in he’d sit and wait for his indulgence, his shepherd eyes human, almost penitent. He never jumped up on me, ever; maybe Louie had taught him not to, maybe not.

I’d walk around the station yard looking at Chevys up on blocks or at rusty oil pans piled in the corner, or spent car batteries, and Dino would walk right beside me, as if I were a blind boy who needed help. Then my dad would see me and he’d smile and pet Dino and then we’d go up to eat.

Then Armstrong and Aldrin stepped onto the face of the moon and stole my attentions, filling me with pride and wonder and distracting me from the lonely death of a dog in a gas station who had, out of boredom, chewed on a car battery in the night, alone.

Togo

My mother’s parents went from Mussolini to Eisenhower in 30 years. When you sat with them you could sense it, the quiet pride, the sense of achievement and good fortune. Even as a kid I remember how it made me feel proud. Then in 1956, after saving for 25 years, they moved from a tenement in lower Manhattan to a brick duplex in College Point, Queens, a good, safe neighbourhood. My grandfather finally got the yard he’d wanted, to grow figs and tomatoes and basil and whatever else would help him remember being a kid in Basilicata.

Next door lived my friend Anthony Galluccio, a few years older, a guitar player, a good guy. He had Togo, a Siberian Husky named after the great Japanese admiral who’d destroyed the Russian navy in 1905, during the Russo-Japanese war. It was an appropriate name for the big Husky, a stoic, reserved fellow with cerulean blue eyes and a lordly manner.

Particular about whom he called friend, Togo was the first dog to ever growl at me, and one of the few dogs I’ve loved who considered me immature, perhaps even insolent. It was an education in humility for a dogless, dog loving boy.

The homes on that street had second-story terraces overhanging the garages. Closed in by wrought iron fencing and accessible by a flight of concrete steps, it is where Togo spent several hours of his day, at least in good weather. He had a plush dog house up there, food and water, and shade if he needed it.

I’d spent two summers with my grandparents there in Queens, after my mother passed in 1971. Anthony and other boys in the neighbourhood were my pals; we’d play handball down at the schoolyard, walk over to Pizza D’Amore on College Point Boulevard, or maybe ride the bus into Flushing, just to walk around. But my favourite thing to do was hang out with Togo on his terrace, listen to a Mets game on the radio, chew bubble gum and watch the cars and people pass by.

At first he resented me invading his world. The king of his terrace, if I got too chummy he’d let me know with a growl, or a quivering lip. Sometimes the lip lifted high, sometimes low, sometimes just a tremor only I could see. After a while, I think it almost became a game with him- a serious game, but a performance nonetheless, one he’d usually end with a lick or a yodel.

Once Anthony or his mom began to let me feed him or play ball with him in the yard, he warmed up and let me into his discerning heart. He knew me as his peculiar little friend, nearly quiet as himself, nearly as discerning.

Into my teens, I lost my intimacy with him. Seeing him only once each week and interested in other things, I’d stop by to say hello, and he’d stare me down and take a treat or two, then retire to his dog house, the novelty of the quiet little boy worn off for him.

When he reached seven or eight, he developed a terrible case of irritable bowl syndrome, requiring a radical diet change, and a regimen of medications he was just not fond of. He became sick and dour, and I recall thinking that I would have, too, if I’d had to suffer through what he did.

Togo passed in his eighth year. He’d been a discriminating dog, like a mentoring dragon to me. Anthony left Togo’s dog house up on the terrace for a good while, and that year I remember going up and sitting on it, watching traffic fly down 14th Avenue, and listening to the Mets get slaughtered by the Phillies.

Micky

Micky was a spaniel mix I’d met in college in 1974, on the east end of Long Island. A black-and-tan 40-pounder owned by my friend Mike, Micky would be let out in the morning, and let back in at night. In between, he pretty much did whatever he wanted.

One of the smartest dogs I’ve ever known, Micky and I met one day in a huge, sandy college parking lot. I saw him from two hundreds yards off, his silky black spaniel ears bouncing up and down as he trotted toward me. Not rushed, but certainly not ambling. Then he slowed, walked right up, bit me on the ankle, and casually walked away.

That’s how Micky introduced himself to all of Mike’s male friends. He’d nip you, smile, then walk off. No grudges afterwards, not even a hint of apprehension or regret; he just felt that, to properly introduce himself, he needed to break some skin.

Micky was the official campus dog. No one even thought of him as a dog, really- he was more like Mike’s canine avatar. He’d wait outside of a building for Mike to come out, or take off to visit someone on the other side of campus—he did whatever he wanted to do. Today I shudder at giving a dog that level of independence, but back then, with the rural, contained setting, the fact that everyone knew and loved him, and his incredible street smarts—well, it just seemed normal.

More than any other dog except my own beloved Lou- the subject of my memoir Last Dog On The Hill- Micky taught me how unbelievably independent, smart and capable certain dogs can become, if given the right environment and owner. He often had other dogs follow him around, dogs twice his twice, half his size- it didn’t matter. Somehow they knew he’d lead them to something good, something doggish. We don’t get to see this much anymore except on farms, or in deeply rural environs. I know we need to watch out for our dogs, but, well—it’s just too bad we can’t have smartass guys like Micky roaming around anymore.

When Mike went off to veterinary school in Manila, we all sort of lost touch with Micky. Maybe Mike’s family in Boston took him—I don’t know. I wish he would have offered Micky to me- I would have taken him in a second.

Meat Bag Betty

I bought Betty from a guy selling puppies out of the back of his rusted Fairlane station wagon back in 1978, while I was working the graveyard shift at a Crown gas station in Southampton, Long Island. The guy could barely stand up; he looked like a pin cushion and probably would have eaten Betty in a day or two, so I gave him five bucks and took the little terrier mix, kept her for a month, fed her way too much and got her fat, then found a college student willing to take her home to a nice spread near Oyster Bay, Long Island. I never saw her again but I’m sure she’d been thankful for me not letting that junkie eat her.

It wouldn’t be until 1989, when I was thirty-three, that I’d officially get my first dog, a six month-old feral Rottweiler mix rescued off of a marijuana grow in Mendocino. He would be my first, and amazingly my best dog- and perhaps the greatest dog of modern times. To learn his story, you’ll need to read the book.

But Lou and I owe a debt of gratitude, not only to Lassie and Old Yeller and Rin Tin Tin, but to those real dogs who’d flickered in and out of my life, dogs who’d touched me, helped me, loved me, kept me wanting. My ghost dogs, gone but not forgotten.

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.