William Wegman

How a coin toss sent art to the dogs

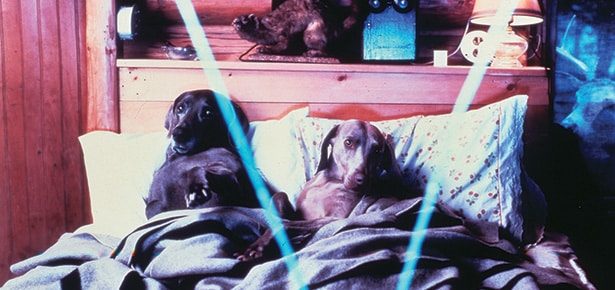

WILLIAM WEGMAN IS ONE OF THOSE LUCKY PEOPLE WHO GETS TO TAKE HIS DOGS to work. In fact, his dogs are central to his work. Wegman’s brilliantly composed, near-iconic images of his Weimaraner companions have earned the artist-photographer-videographer wide success and international acclaim. His photographs range in style from high art and near-abstraction to playful images of the dogs dressed in human costumes—sometimes as characters from nursery rhymes or fairy tales. But serious or whimsical, there is a painterly artistry in every one of Wegman’s photographs, an attention to light, form, texture and composition that is as much a signature of Wegman’s work as his sleek, silver-toned subjects.

Wegman didn’t start out taking pictures of dogs; in fact, it was not his intention to become a photographer at all. As he explained in a recent interview, “It kind of started in the ‘70s when I got a camera to document some of these ‘happenings’ I was orchestrating. I remember floating styrofoam letters down the Milwaukee River, and I stood over the river at another point and photographed them as they passed under. Over time I started to get concerned with how the photographs looked, and I thought that was kind of a contradiction between my actual motives and what I ended up with. So there was a point where I got to realize that I should be making things for the camera as opposed to finding things for the camera. That was a fundamental difference; that was a ‘eureka’ manifesto moment.”

It wasn’t long before Wegman became an important presence in art circles, but it would be years before an irrepressible Weimaraner pup named Man Ray squirmed his way into Wegman’s world, changing his life and his art forever. Looking at his work now, it would be easy to assume that Wegman chose to get a Weimaraner specifically for the aesthetic qualities it could contribute to an image, but that was not the way it happened at all. “I got Man Ray for Gayle, my wife at the time, who wanted a big, short-haired dog. She liked Dalmatians and German Shorthaired Pointers—and then we came across an ad in the paper that said ‘Weimaraners, $35.’ We took a look and there was this one boy that really caught our fancy. He was about six or seven weeks old and we brought him home. I still wasn’t sure that we were going to keep him, so I had to flip a coin. Tails dog, heads no dog.” Fortunately for Man Ray, for Gayle (we assume) and for Wegman’s legions of fans, the coin came up tails five times in a row.

As for Man Ray becoming a photographic subject, that wasn’t entirely Wegman’s idea either. “I was setting things up in my studio and the dog would kind of get in my way. I’d tie him up but he’d start whining, so I’d let him loose, and he always seemed to want to be in the space that I was activating with these objects I was photographing. So I did take his picture and figured out ways to include him now and then, and he was always very happy when that happened.” The rest, of course, is art history.

Man Ray died in 1982, but Wegman has since owned and photographed a number of other Weimaraners, all of whom have been enthusiastic participants in his work. “There’s something about the breed that wants to do it,” says Wegman. “I’ve had so many Weimaraners now and I know it’s true. This really is a breed that likes—almost needs—to have a job, and I think that because I do it, they want to do it too.” Some people have expressed concern at the thought of dogs putting in hard hours under hot lights wearing uncomfortable costumes, but Wegman assures us that this is not at all what goes on. As he explains, “The dogs tend to hang out on the couch or roughhouse with each other, meet other people, fool around and do doggie things, but when they’re called to go up, they do. They sort of trot up to the set, and they’re placed up high, usually, if we’re making them tall. Then they sit there for 20 or 30 seconds while all the costuming is readied. If you can imagine putting a blanket loose, on a horse or a dog, it’s no more confining than that because we open up the costumes so that they’re not really as contained as they appear to be. Then I take the picture, and the dogs get down. It’s a few seconds for them, though it’s hours and hours for us.”

There is an animal welfare issue connected with his dog photographs that concerns Wegman, however, and that is the matter of a breed becoming popular or trendy because the public sees it in a movie, on TV, or in this case, in art photography. Says Wegman, “I hope people don’t get Weimaraners because of seeing them in my photographs. I hear that there are too many and that people are breeding them and thinking that because they’ve seen my photographs, all they have to do is kind of look at the dogs and they’ll be happy. My dogs are happy because I engage them very fully. I don’t leave home without them. I really don’t want people to get misled because the truth is, Weimaraners are wonderful, but they’re very demanding and require more than the usual amount of your attention.” The complex and demanding nature of the Weimaraner may make it an inappropriate pet for many people, but for Wegman, it is an endless source of inspiration. “Each one of my dogs brings a different personality, which gives me new ideas,” he says. “That’s why I’ve been able to engage them for so long and still be interested in it. I have a new dog named Penny now who is completely different than the others. She’s very sweet and just exceptionally pretty, and kind of fragile in a way. I’m taking lots of interesting pictures of her, and it’s really exciting to work kind of within the same area but find something new in it. I hope I’m not making people sick of these damn Weimaraners, but it’s hard to stop, really.”

Ask the art critics, museum curators, dog lovers and other fans of Wegman’s work, and they will undoubtedly say they hope he never stops.

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.