Your Dog’s Amazing Nose

With their incredible sense of smell, sniffer dogs are detecting everything from early-stage cancer to missing persons and pets

Though Katie Valaas’ beloved orange Tabby, Norm, was predominantly an indoor cat, he was lucky enough to enjoy some outdoor time in his Seattle neighbourhood thanks to a harness and retractable lead. Unfortunately, on one of these outings, Katie set Norm’s lead down momentarily to tie her shoe and the cat took off running, the plastic handle of his leash bumping along behind him. Katie searched her own and her neighbours’ yards to no avail—two days later, in the midst of a sweltering summer heat wave, Norm was still missing. She decided to call in an expert.

“Katie found out about our group, the Missing Animal Response Network (MARN), and one of our handlers, along with her dog, a Dachshund mix named Harley, responded to her call,” explains Kat Albrecht, a former police officer with years of experience training and handling sniffer and detection dogs for use in criminal work. “When we got to the area where Norm was last seen, Harley immediately zeroed in on a hot tub in the yard and started going absolutely crazy with excitement, as per his training as a cat-detection dog. When his handler looked under the hot tub, sure enough, there was Norm—he’d been there for three days, without food or water and with his lead hopelessly wrapped around the machinery, trapping and, in fact, nearly strangling him. They had to cut him out of his collar. I have no doubt that Harley saved Norm’s life that day.”

Kat, who is currently based on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada, founded MARN after her own police bloodhound, AJ, dug out of her backyard and went missing in the woods. Desperate to find him, Kat called up a friend with a Golden Retriever who had been trained to track down missing persons using his sense of smell—the dog found AJ in 20 minutes flat. That moment changed Kat’s life forever.

There is a difference, she explains, between the way a dog is trained to find a lost cat versus a lost dog. In the former case, the detection dog is trained to seek out all cats in an area, and alert its handler to the presence of any cat so that he or she can determine whether it is, indeed, the cat in question. When it comes to lost canines, a detection dog is trained to follow the missing dog’s unique scent based on a provided scent article—a blanket or toy used regularly by that dog—and ignore the scents of all other dogs.

The common ground, of course, is scent.

“Their sense of scent is amazing—so much stronger and more powerful than our own,” Kat says. “They have the ability to discriminate between scents, to tell the difference between one dog, or one person, and another.”

Cindy Otto, director of the Penn Vet Working Dog Center at the University of Pennsylvania, agrees, adding that, when it comes to dogs, “their whole system is geared to ‘see’ the world through their noses.”

“When it comes to their olfactory abilities, there is plenty of data, lots and lots of facts, around how dogs differ from humans, from the physical level right down to the molecular,” Cindy says. “But, when it comes to harnessing this incredible sense of smell and using it to perform practical and even lifesaving services, the biggest thing that sets canines apart is their ability and desire to work with people and to be trained to perform certain functions. Bears, for instance, have an even better sense of smell than dogs—vultures, too. But I don’t know many human handlers who would be comfortable partnering with a 600-pound Grizzly, and vultures, as far as I have seen, aren’t really interested in putting in a long day at the office.”

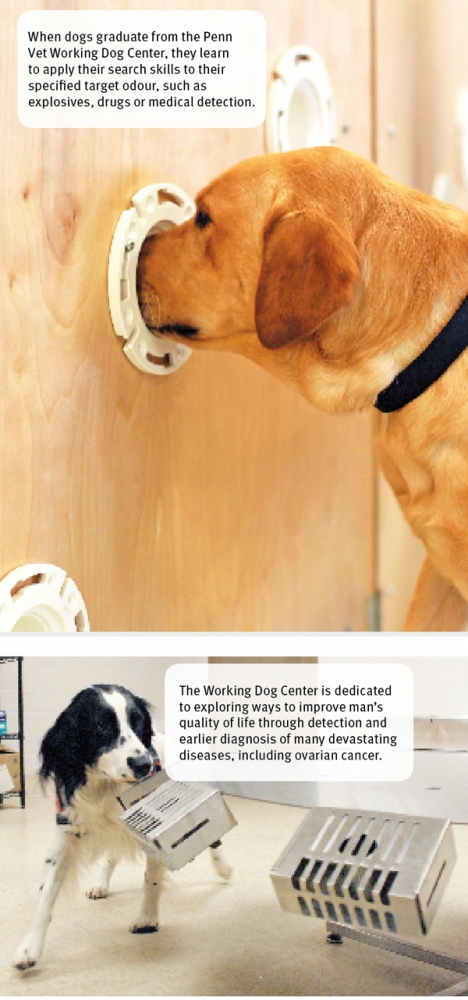

To that point, the Penn Vet Working Dog Center is dedicated to harnessing the unique strengths of our canine partners, producing elite scent-detection dogs for public safety and health.

“A detection dog is a dog we partner with to identify a specific scent on which, generally, they’ve been trained,” Cindy explains. “We raise and train detection dogs here at the center from the time they’re eight weeks old in a sort of ‘liberal arts’ degree, where they learn to find an odour. It doesn’t matter what the odour is at the earliest stages of training—it could simply be a chemist-made universal detection compound. We’re simply interested in teaching them the process of finding this smell using their nose.”

This, she says, is done by teaching puppies how “fun” it is to explore the world using their nose, and by rewarding them, usually through play, whenever they hit on the control scent. This allows the Penn Vet team to, as the dogs mature, help them find their “career path,” whether that be explosives, drug, arson, cadaver, diabetes or cancer-detection work, by eventually introducing them to the scent corresponding to that specific line of work.

“The range of jobs these dogs have is mind-boggling—and ever growing as we continue our research,” says Cindy. “Off the top of my head, I can think of dogs who use their sense of smell to detect bombs and narcotics, who perform search-and-rescue work to find both survivors and human remains, who detect cell phones in prisons and who can find large amounts of concealed money. As we build more and more of these large pipelines across North America and the world, we’re starting to train dogs to detect leaks to prevent major environmental disasters. There are dogs who detect peanuts, helping children who suffer from major allergies, and conservation dogs who, with their noses alone, find either endangered or invasive species. There are dogs who detect smuggled ivory and, in our own work here at the center, we’re about to launch a study to see if dogs can detect stolen antiquities smuggled into the U.S. from Syria. The craziest detection work I’ve heard of, however, are the dogs that are trained to sniff out scat in the ocean in order to help scientists learn more about marine mammals like whales. Anything that emits a scent—and most things on this planet do—a sniffer dog can be trained to detect.”

Scent-detection canines are also doing important work in the health arena, with service dogs helping people who suffer from a range of medical-related issues, including diabetes, seizures, and migraines, better manage their conditions. Mary McNeight of Service Dog Academy in In Waterloo, Illinois, has helped to train more than 150 medic alert dogs to provide support to people who live with and suffer from diabetes, narcolepsy, seizures, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), migraines, hypoglycemia, and atrial fibrillation.

“We know that 40 percent of a dog’s brain is devoted just to their nose, giving them a smelling capacity more than 250 times greater than our own,” she says. “To give an example, a dog can smell a single drop of blood in a swimming pool filled with water—this, in turn, means that dogs can be trained to detect, via scent, the biological changes that happen in our bodies before, say, a migraine or a seizure is about to hit, giving people the time to prepare to deal with that situation accordingly.”

This means that someone who suffers from migraines has a chance to get to a safe place and to take his or her medication before the headache hits. A person who has diabetes, alerted by a dog to changes in his or her blood-sugar levels,

is able to get food and medication—such as glucose tabs, insulin, juice, and meters—to rectify the situation before it becomes life-threatening.

The training, Mary says, is “almost identical for all the dogs—it’s the actual scent that is different.” However, for all of the disabilities that Service Dog Academy trains canines to detect, she emphasizes that “there’s a cascade of organic compounds exhaled off the breath and sloughed off the body, and our job is to teach the dog what’s important to pay attention to and what to ignore.”

While Mary’s medic alert dogs are trained to work with and for a particular individual, other types of detection dogs perform scent work that benefits many members of the public. In Gatineau, Quebec, Canada, Glenn Ferguson handles a team of canines who have been trained to detect cancer in its early stages, working off of the theory that cancer cells undergo a distinct metabolic process different than normal cells, consuming glucose at a much higher rate than their healthy counterparts and thus giving up different waste products that have a distinct smell.

“The first major department we worked with was in Chicago, and we’ve since gone on to test 30,000 firefighters in total—10,000 in the last year alone,” he says. “Our dogs are trained to identify the odour of cancerous and pre-cancerous cells by comparing and contrasting a lineup of five to six breath samples, one of which is known to be cancer, on what we call a sniffing station. We use a food reward to do this training—in fact, none of our dogs has a bowl, this is how they’re fed their meals and that makes them very motivated to do the work.”

When it comes to evaluating the samples of firefighters, Glenn likens it to a “mass screening process, sort of like luggage going over a carousel at the airport.” Breath sample kits, including a surgical mask that is worn for 10 minutes over the mouth and nose and then put back in an odour-proof pouch, are distributed to firefighters across North America, used sealed, and sent back to CancerDogs’ headquarters, where they are “worked” by the dogs. If any member of Glenn’s canine team picks up on a cancerous or pre-cancerous sample, the firefighter to whom the sample belongs is notified so that he or she can take the necessary next steps, such as consulting with their doctor or a specialist and making changes to their diet or lifestyle.

“People can be warned and take proactive measures when it comes to cancer, and that’s our aim in our work with these dogs, who are often detecting the disease two to three years before it can be found via imaging,” he says. “We have, however, had some people who have had serious cancers uncovered, whose survival was definitely in doubt, but for the most part we are trying to protect people, well ahead of time, from that late-stage diagnosis. For us, that’s a real success.”

Our dogs are trained to identify the odour of cancerous and pre-cancerous cells by comparing and contrasting a lineup of five to six breath samples

Cancer aside, dogs—and their wonderful noses—are also incredibly useful when it comes to search and rescue operations. In the mountains of Canada, avalanche rescue dogs work to detect and pursue people who have been buried under the snow. Kyle Hale, president of the Canadian Avalanche Rescue Dog Association, says that with training from his organization, teams of dogs and handlers are deployed throughout the provinces of B.C. and Alberta when such disasters occur.

“The thing about these dogs, beyond their outstanding sense of smell, is that we’re able to send them into these very high-risk, volatile areas and circumstances to do the work of many people in a fraction of the time,” he explains. “We train the dogs from a very young age using a relatively simple game of hide-and-seek, where the dog is, essentially, rewarded for solving a problem, and making that problem harder and harder to solve. Eventually, the dogs are able to detect human scent below a surface, and to dig through to the source of the scent. Though we highly recommend anyone going into an avalanche-prone area wear a transceiver in case something happen, in cases where this technology isn’t present, the dogs are another extremely useful tool we can use to find someone who has been lost and buried.”

Unfortunately, when it comes to avalanches, most recovery efforts involve victims who are deceased. Over at the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation (NDSDF) in Santa Paula, California, the objective is different.

“Our dogs are trained to search for live scent, meaning they’re only using their noses to find survivors of major disasters, to ensure no one is left behind,” says NDSDF Marketing and Communications Officer Denise Sanders. “The dogs are able to say there’s someone here, under the rubble, who is still alive, or, alternately, there are no survivors left here, so we need to move on.”

NDSDF rescues its dogs, including German Shepherds, Golden Retrievers, Border Collies, and Belgian Malinois, from shelters, trains them, and partners them with a first-responder handler to do search-and-rescue work at a range of disaster sites, like Ground Zero in New York after 9/11 and Haiti following the 2010 earthquake.

“We have trained 190 teams since 1996 and currently have 69 active teams across the country, and there’s still more needed,” Denise says. “Any time these big disasters happen, whether it’s a hurricane or a mudslide, the communities and countries affected could definitely use more of these dogs, with their incredible sense of smell, to cover more ground more quickly—and, ultimately, save more lives.”

Back at the Penn Vet Working Dog Center, Cindy Otto agrees.

“We know there’s a shortage of detection dogs in the U.S.,” Cindy says. “The fact is, most of these dogs are currently being imported from other countries, and there’s actually a big move in Congress at the moment and among people in the industry that feel these dogs need to come from local, domestic sources so we can influence their health and genetic welfare to a great degree. So often, in so many situations, we are putting human lives in these dogs’ hands—or, as it were, their noses—it’s important we utilize their unique ability and take care of them to the utmost degree.”

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.