How To Tame a Fox—and Build a Dog

The amazing true story of how a pair of scientists condensed the domestication process by thousands of years and made foxes every bit as loyal and tame as dogs

Suppose you wanted to build the perfect dog from scratch. What would be the key ingredients in the recipe? Loyalty and smarts would be musts. Cute would be as well, perhaps with gentle eyes, and a curly, bushy tail that wags in joy just in anticipation of your appearance. And you might toss in a mutt-like mottled fur that seems to scream out "I may not be beautiful, but you know that I love you and I need you."

The thing is, you needn't bother building this. Lyudmila Trut and Dmitri Belyaev have already built it for you. The perfect dog. Except it's not a dog, it's a fox. A domesticated one. They built it quickly—mind-bogglingly fast for constructing a brand new biological creature. It took them less than sixty years, a blink of evolutionary time compared to the time it took our ancestors to domesticate wolves to dogs. They built it in the often unbearable minus 40F cold of Siberia, where Lyudmila and, before her, Dmitri have been running one of the longest, most incredible experiments on behaviour and evolution ever devised. The results are adorable tame foxes that would lick your face and melt your heart.

Many articles have been written about the fox domestication experiment, but a new book, How To Tame a Fox {and Build a Dog} (2017, University of Chicago Press), from which this article is adapted, is the first full telling of the story. The story of the lovable foxes, the scientists, the caretakers (often poor locals who devoted themselves to work they never fully understood, but would sacrifice everything for), the experiments, the political intrigue, the near tragedies and the tragedies, the love stories, and the behind-the-scenes doings. They're all in there.

It started back in the 1950s, and it continues to this day, but for just a moment travel back with us to 1974.

One clear, crisp spring morning in that year, with the sun shining on the not yet melted winter snow, Lyudmila moved into a tiny house on the edge of an experimental fox farm in Siberia with an extraordinary little fox named Pushinka, Russian for "tiny ball of fuzz." Pushinka was a beautiful female with piercing black eyes, silver-tipped black fur, and a swatch of white running along her left cheek. She had recently celebrated her first birthday, and her tame behaviour and dog-like ways of showing affection made her beloved by all at the fox farm. Lyudmila and her fellow scientist and mentor Dmitri Belyaev had decided that it was time to see whether Pushinka was so domesticated that she would be comfortable making the great leap to becoming truly domestic. Could this little fox actually live with people in a home?

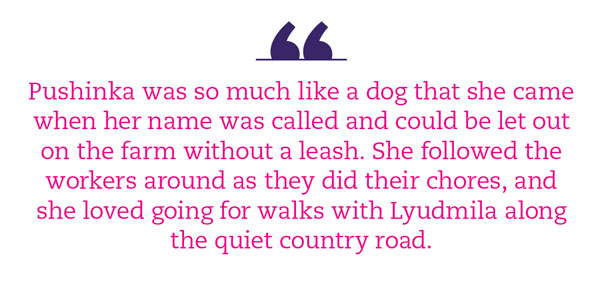

Belyaev's plan for the experiment was audacious. The domestication of a species was thought to happen gradually, over thousands of years. How could he expect any significant results, even if the experiment ran for decades? And yet, here was a fox like Pushinka, who was so much like a dog that she came when her name was called and could be let out on the farm without a leash. She followed the workers around as they did their chores, and she loved going for walks with Lyudmila along the quiet country road that ran by the farm on the outskirts of Novosibirsk, Siberia. And Pushinka was just one of the hundreds of foxes they had bred for tameness.

By moving into the house on the edge of the farm with Pushinka, Lyudmila was taking the fox experiment into unprecedented terrain. Their 15 years of genetic selection for tameness in the foxes had clearly paid off. Now, she and Belyaev wanted to discover whether by living with Lyudmila, Pushinka would develop the special bond with her that dogs have with their human companions. Except for house pets, most domesticated animals do not form close relationships with humans, and by far the most intense affection and loyalty forms between people and their dogs. What made the difference? Had that deep human-animal bond developed over a long time? Or might this affinity for people be a change that could emerge quickly, as with so many other changes Lyudmila and Belyaev had seen in the foxes already? Would living with a human come naturally to a fox that was so domesticated?

The 700-square-foot house had three rooms in addition to a kitchen and bathroom. Lyudmila had moved a bed, a small couch, and a desk into one room to serve as her bedroom and office combined, and she had built a den in another room for Pushinka. The third room was used as a common area, furnished with a few chairs and a table, where Lyudmila ate her meals and where, on occasion, research assistants or other visitors could gather. Pushinka would be free to roam throughout.

As Lyudmila would discover over the course of many months with Pushinka, the lovable little fox would not only become perfectly comfortable living with her, she would become every bit as loyal as the most loyal of dogs. Pushinka's tale was only beginning. She and Lyudmila would live through much together, as would many of the other foxes and many of the other researchers working in Siberia, for this bold experiment in domestication was only just starting to reveal all the wonders it would serve up for science.

For more, see Lee Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut's new book How To Tame a Fox {and Build A Dog}.

Excerpt modified from Lee Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut's 2017 book How To Tame a Fox {and Build A Dog}, The University of Chicago Press

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.