Not Your Typical Grandma

The National Disaster Search Dog Foundation's founder Wilma Melville

The field Melville chose was also unusual, especially at the time: disaster search. Disaster search dogs are trained to use their powerful noses to find people buried alive during disasters like earthquakes, floods or bombings then alert their handlers and rescue teams. Melville and her black Labrador Retriever, Murphy, trained with Pluis Davern in California to work toward an advanced disaster search dog certification from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which they achieved before Murphy turned two.

In April 1995, when Melville was 62, she and Murphy were deployed to the Oklahoma City bombing that killed 168 people and injured more than 680 others.

Suddenly, working with a search dog was no longer a hobby.

The disaster was horrific. And Melville was shocked by how few search teams brought trained canines, and to learn there were very few FEMA-certified dogs in the United States.

“I was horrified at the state of affairs,” she says. “I couldn’t believe that task forces came with no dogs. I couldn’t believe that a couple of task forces came with pet dogs. I said, ‘What’s happening here?’”

Back home in Ojai, CA, Melville decided something had to be done to rectify the situation—and that she was the person to do it. She realized she had the perfect background: not only was she a certified search dog handler but as a former teacher she could write an effective training curriculum. So she founded the nonprofit National Disaster Search Dog Foundation (SDF) with the mission to rescue dogs from shelters, train them as disaster search dogs, and pair them with firefighters and first responders—all for free and without any government funding. One basic principle got the ball rolling.

“You have to have the right dog,” Melville says. “The number one characteristic is drive. And what is drive? Drive is a dog who must have a job and who makes that clear to you.”

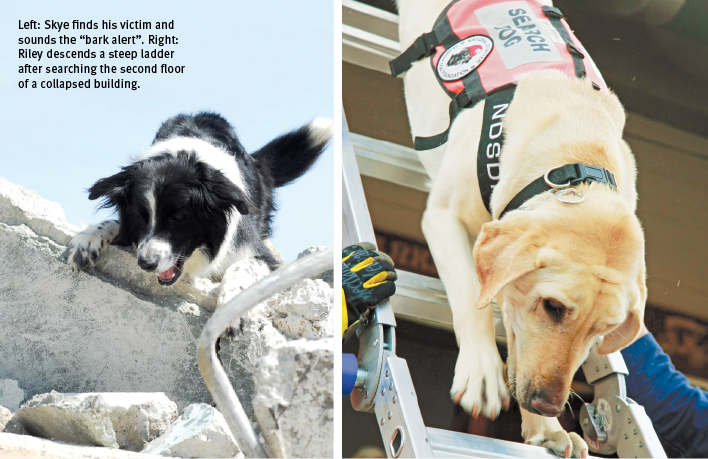

She said successful dogs are athletic, focused, bold, self-confident, and energetic and will walk on any kind of footing since they have to search on rubble, metal, and wood (training is often held at recycling centers). And they won’t quit—whether it’s retrieving a toy or searching for a person.

“Any dog who is going to succeed has to love it,” Melville says. “They would love any kind of work that you gave them. With positive reinforcement they’re trained, and they just have the greatest life.”

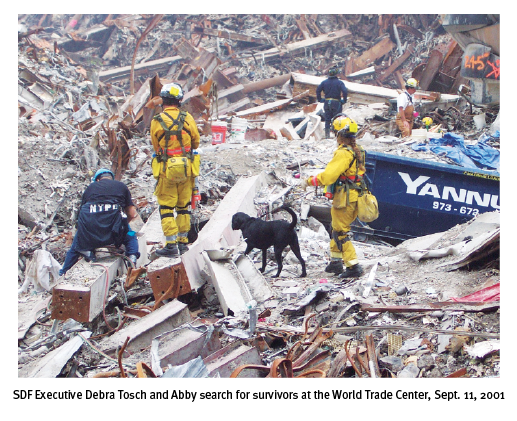

What she thought would be a six-month project became her life’s work. SDF has trained 160 search teams that have been deployed to 118 disasters and missing person searches around the world, including 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, the 2010 Haiti earthquake, and the 2011 Tohuku earthquake and tsunami in Japan. Plans are in the works to continue expanding with the opening of a National Training Center on 125 acres of donated land in Santa Paula, CA.

Melville says one of the rewards of the success of SDF is to see “a dog that was tossed onto the trash heap” transform within nine months of SDF training to being skilled, happy, healthy, and attached to a handler with a real appreciation of their canine partner.

“When you see the respect that the handler has for the dog, you know you have a good team,” Melville says.

The volunteer handlers are usually firefighters who take on a dog in addition to their regular duties. Firefighters are ideal candidates to be SFD handlers because they are often the first to arrive at a disaster scene, are trained to cope with responding to a crisis, and their work schedules allow them to train with their dogs much more often than most civilians. To ensure a good match, SDF also interviews the family of a potential handler to make sure they would accept a dog into their home and support the firefighter in taking on extra, unpaid work. Once a handler is accepted into the program, SDF trains them to learn to work with their new dog to help build a successful team.

“The right dog is critical. The right handler is critical. And then both of them have to get the best training possible,” Melville says.

“Our canine teams responded to the Haiti earthquake as part of the Los Angeles County Urban Search and Rescue Team, which found and rescued 12 survivors that were buried in rubble. The dogs worked very well and played a big part in several of these rescues. We are very proud of these teams and the work that they did in Haiti,” Heritage says.

She’s witnessed many other “live finds” in her deployments as well.

“There is nothing like it—tears, goosebumps, camaraderie, exhaustion, and validation,” Heritage says. “It is incredible.”

Not only do the dogs help find survivors but they can bring comfort to other rescuers and onlookers who might need a few moments with a dog. And the dogs themselves enjoy the work. Heritage says her current partner, a seven-year-old German Shepherd named Asta, “lives” for the opportunity to work.

Asta attends SDF training sessions each week to keep her skills sharp. She also teaches new handlers how to read behaviour and practice new skills. Handlers have to learn to trust their dogs because time is so critical in disaster search, so handlers must listen not only when a dog finds a survivor but also when the dog indicates no one is there so that they can search elsewhere.

She says because no two disasters are alike, she always gets new ideas for training from deployments. In addition to basic obedience, she and her team train SDF dogs to learn to search off-leash for multiple victims who are completely buried and concealed from view. When they find a scent, they follow it to the exact location and bark at the spot until the handler arrives and gives a reward. The dogs also learn “extreme agility skills” involving ladders, chain link, tunnels, crawls, and wobbly props, and “direction and control,” in which the dog can take hand, voice, and/or whistle commands at a distance to move farther away, right, left or recall in a large field without distraction.

“Our dogs have been screened for very high toy possession, prey, and hunt drives… we allow the drives of the dog and his or her extreme desire for the reward to lead the dog into the behaviours we are looking for,” Heritage says. “It’s easy with the right dog!”

“They are like racehorses: very hard to contain unless they have a place to focus all that enthusiasm. That puts them into shelters and often on the euthanasia list. When I think of all the incredible dogs that we have trained here and what their fate would have been, it’s overwhelming,” Heritage says. “We watch dogs that had no idea what self-control is turn into finely tuned, highly driven working dogs and it’s breathtaking. They have a purpose—a destiny to do great things.”

Visit searchdogfoundation.org for more on the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation.

Join the newsletter and never miss out on dog content again!

"*" indicates required fields

By clicking the arrow, you agree to our web Terms of Use and Privacy & Cookie Policy. Easy unsubscribe links are provided in every email.